- Home

- David Levithan

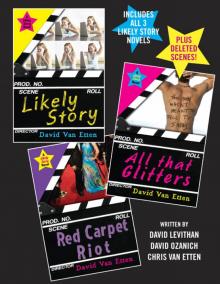

Likely Story!

Likely Story! Read online

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Likely Story copyright © 2008 by David Levithan,

David Ozanich, and Chris Van Etten

Likely Story: All That Glitters copyright © 2008 by David Levithan, David Ozanich, and Chris Van Etten

Likely Story: Red Carpet Riot copyright © 2009 by David Levithan,

David Ozanich, and Chris Van Etten

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States of America by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

The works in this collection were originally published separately in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf in 2008 and 2009.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Etten, David Van.

Likely story! / David Van Etten. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-375-89685-9

I. Title.

PZ7.V2746Li 2010

[Fic]—dc22

2009030777

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.0_r1

Contents

Likely Story

All That Glitters

Red Carpet Riot

About the Authors

BOOK ONE

My life has been a soap opera since the day I was born.

At the time of my arrival, my mother had been an actress (using that term loosely) on Good As Gold for almost ten years. The writers had worked her pregnancy into the story line, and when Mom started going into labor, the director kept the cameras rolling. Mom swears she didn’t notice, but if you look at the episode, you can see that she’s playing it up, hoping that each contraction will bring her closer to a Daytime Emmy. Luckily, the cameras weren’t allowed in the delivery room. But two weeks later, Mom was back at work, on the twelve-by-twelve set that serves as every single hospital room in the fictional town of Shadow Canyon. (If you watch closely, you’ll see that only the flowers change.) Immaculately made up, with the whole staff of Shadow Canyon General watching on in admiration, my mother gave birth to me for a second time. And I was there waiting, under the sheet between her legs, for Dr. Lance Singletary to reach in, lift me toward the camera, and utter with complete surprise, “It’s a girl, Geneva! It’s a girl!”

This was the first time I ever appeared on TV.

It was also the last.

They wanted to keep me. Mom and I were on the cover of Soap Opera Digest and Soap Opera Weekly. There was a crew from Entertainment Tonight taping the Good As Gold crew as they taped my second birth. Mom’s fan clubs sent thousands of daisies, homemade cards (many of them addressed to Geneva), and home-knit pairs of socks. A network press release dubbed me “the Future Queen of Soapland” and said I was a “star of tomorrow.” The hype was stupendous, but clearly I didn’t believe my own press. On my second day of taping, I refused to stop crying—big, volcanic wails. The noise was unbearable … and, even worse, the way I cried made my face scrunch up. If there’s one thing a soap opera will never, ever tolerate, it’s a scrunched-up, uncute face, even on a sixteen-day-old baby.

A supermodel pair of baby twins was brought in, and I was sent home with a nanny. Four months later, Good As Gold viewers would watch as Geneva’s infant daughter, Diamond, was abducted by Geneva’s escaped-convict ex-lover, a former priest named Rance who had sixteen personalities (ten of whom were battling sex addiction). When Diamond was found six months later by the lone member of Shadow Canyon’s police force, she had miraculously transformed into a breast-budding twelve-year-old starlet—a fact that none of the citizens of Shadow Canyon (not even the clairvoyant ones) ever noticed.

In the past sixteen years, Diamond has been abducted six times, has died once, has fallen in love twice with people who were later revealed to be her relatives, has had three bouts of amnesia, has been in a coma twice, has eloped once, has broken off two engagements, has had her debutante debut ruined once by an earthquake and once by a dead best friend, has twice fallen into the hands of a coven of witches, has been locked in the trunk of a car six times, has pulled a gun on someone fourteen times, has had a gun pulled on her twenty-two times, and has had near-death experiences eight times (twice from drowning, twice in a car crash, once in a plane crash, once after being stabbed by her lover-slash-long-lost-stepbrother, once in childbirth, and once—I swear to god—from slipping on a patch of black ice, which was later revealed to have been put there by her diabolically scheming half sister/stepmother).

The one thing Diamond and I have in common: Neither of us knows who our father is. Everyone has a theory. Personally, I’d like a name.

Really, it’s only compared to Diamond’s life that my own life seems ordinary. By most other standards, it’s still pretty messed up.

In the past sixteen years, my mother has been engaged four times, has been married three times, and has been sued for palimony twice. We have lived in eleven different places—one for each engagement and marriage, one carriage house, one apartment, one extended stay at the Beverly Wilshire hotel, and one extended stay at an “exhaustion clinic” (chosen because it had day care). I have attended six different schools, have faced off against either nineteen or twenty nannies—I’ve lost count—and have met at least five different men who may or may not be my father.

It’s been a lot to deal with, mostly on my own. Only two things have remained constant. The first is the way I’m treated at school. It doesn’t matter which school, whether it’s full of stoners or preps or aspiring actresses or nuns. They’re pretty much the same once my mom’s identity is revealed. I’ve put up with it all. “Hey, your mom is sleeping with the mayor of Shadow Canyon even though he’s married to her sister!” “Hey, how’d your mom like having sex with a guy who ended up being a ghost?” “Hey, isn’t your mom the one who was abducted by aliens and came back with a pack of dynamite strapped to her bra on a brainwashed mission to blow up the Shadow Canyon Mother-Daughter Fashion Show?”

Yes, that’s my mom.

Uh-huh.

You got me.

Please stop.

You’d think it would be enough to make me loathe soap operas. But, really, I can’t hate them too much, since the second big constant in my life has been the Good As Gold set. The only babysitter or nanny I ever tolerated was Gina, my mother’s makeup person (which makes her a pretty big constant, as well). Not because she let me play dress-up or taught me how to use mascara (I still don’t). No, I loved Gina because she would let me sit in the space beneath my mother’s makeup table so I could read as much as I wanted. I would alternate between Little Women and all the gossip magazines; a lot of the time I learned more about my mother from Us Weekly than I did from our us-weekly dinners. I also loved to read my mother’s scripts, because each one was more melodramatic than the next. At school I learned addition, subtraction, multiplication, and long division. After school I learned seduction, distraction, manipulation, and long indecision. You’d think it would have made me a little slut. But ultimately it just made me want to write about little sluts.

The older I got, the more I realized how ridiculous Good As Gold was. Time moved very, very slowly in t

he scripts—usually a whole week’s worth of episodes would take place in about three hours of Shadow Canyon time. And in that three hours there’d be everything from murder, sex, and betrayal to feral-cat attacks and gratuitously half-naked coed swim meets. The characters I loathed the most were the teenagers, because they never found the time to go to school or do anything outside their little world. If anything, they were just extensions of their parents’ plotlines. Even when it got a little interesting—ooh, Diamond’s dabbling in lesbianism; wow, Carter’s become addicted to champagne—the plots seemed to exist so the town elders could have more Daytime Emmy Moments of shock! outrage! and grief! As soon as the parents stopped wringing their hands over the trouble the teens had gotten into, the teens were off in search of another form of trouble. (For whatever reason, the Good As Gold writers loved to threaten the teen characters with electrocution. Nothing like a run-in with an open wire to boost ratings.)

It was comedy, but nobody seemed in on the joke.

At first I kept my mouth shut. Then I couldn’t take it anymore.

The big breakthrough came on a day that nobody was expecting even a small breakthrough. It was midnight after a long day of eleventh grade (for me) and a long day of shooting (for Mom), and Mom was watching herself on TiVo. She’ll never admit she does this, but what can I say—she’s addicted to herself.

The scene was pretty harmless, as Good As Gold scenes go. Geneva was talking to yet another ex, Colt, who’d been blinded in a car accident that was caused by either an on-coming truck (driven by Geneva?) or a UFO (driven by Geneva?).

GENEVA

We can’t do this.

COLT

Geneva, you’re the only woman

I would want to see …

if I could see.

GENEVA

You may be the blind one,

Colt, but I’m the one who’s

truly been blind. Blind to

the consequences.

COLT

Hold me.

GENEVA

I can’t! Not with Vance in

the other room!

COLT

If you won’t hold me, then

I’ll hold you.

That’s really all it took to get Geneva into bed. Although at this point in Mom’s career—much to her distress—Geneva always seemed to fall into bed with her clothes fully on.

“Did you really just say, ‘You may be the blind one, but I’m the one who’s truly been blind’?” I asked.

From the resulting silence, I figured Mom hadn’t heard me—she was too busy studying the way she looked as Colt unbridled her. But after the scene was over (which was about ten seconds later, since soap-opera scenes never last longer than it takes to unbutton a shirt), Mom paused the TiVo.

“What?” she said, annoyed.

I knew I was breaking her routine. When Mom watched the TiVo, she always took precise mental notes. Not about what she could do to improve her performance—no, more like who she could blame for whatever was wrong. Her co-stars, the writers, the lighting director, the guy from catering who wouldn’t stop putting potato chips on the snack table—if Mom wasn’t hitting her mark, someone had to burn. I myself never felt too far out of the range of her blame. My whole existence threw her off.

“Don’t you ever get sick of the crap lines?” I said to her now. “Don’t you ever want to sound like a real person instead of someone on a soap opera?”

“A real person? Are you the expert on real people now?” Mom challenged, using her best vodka voice. Absolut bitch.

I continued. “It’s like you’re in this world full of Hallmark sayings, although Hallmark would never, ever use any of them on a card. Dear Colt. I’m so sorry that you’re blind. But I’m the one who’s truly been blind. Come see me sometime for a cure. Love, Geneva.”

“It works” was all Mom had to say to that.

“If it works so well, why are your ratings down?”

The minute I said it, I knew I’d crossed the line … right into my mother’s militarized zone. I was allowed to trash the dialogue—she’d only blame the writers for the purple prose, even though she was the one who stuck the quill so far deep into the purple ink, especially when she “improvised.” I could even, if she was in a good mood, make fun of a costume or the name of a character. But I was never allowed to discuss anything to do with aging, appearance, the Daytime Emmy she’d never won, or bad ratings.

If it had been an episode of Good As Gold, she would have slapped me. But instead she unpaused her TiVo and turned back to her show. She even turned up the volume a little, to punctuate the point.

I figured if she could act like an adolescent, then I (the actual adolescent) could, too. So I went to my room, slammed the door, and pulled out my journal to fire off a few lines. But even that didn’t satisfy me.

I had a blog that I used every now and then—it was pretty low-key, and I thought maybe a dozen people had read it. It seemed like a safe space. So before I could think too much about it, I started to vent.

Why are soap operas so fake? Who the hell wants to spend an hour every day watching amnesiac nymphomaniacs who speak like aliens from the planet Melodrama? What about real problems? What about real drama? Real life is contrived enough as it is. Wouldn’t it be great to have a soap opera about people you actually cared about? Wouldn’t it be revolutionary to revolve a show around all the messed-up crap that actually happens to us instead of all this make-believe crap? My friends’ stories—anybody’s stories—are about a hundred times more compelling than anything you can find on the TV at three o’clock. You want to know why soap operas are going the way of the dinosaur? It’s because we relate to the characters about as much as we would relate to a dinosaur. If I had my own show, I’d be able to prove to you how right I am.

I figured nobody would read it.

It ended up that two people did.

My best friend, Amelia, called me about two minutes after I posted it.

“So you and your mom got into a fight again.” (That was her version of hello.)

“I mentioned her ratings.”

“Whoa! Did you happen to mention that she needs a new face-lift, too?”

“I couldn’t. The TV was too loud. I think the last face-lift might have accidentally covered up her ears.”

“It’s not fair, you know. I wish I could make fun of my parents’ ratings, too. All parents should have ratings to make fun of.”

Amelia and I were somewhere between being old friends and new friends, meaning we’d known each other for about a year, ever since I’d moved to Cloverdale, my latest school. (My mother tended to send me to a new school every time we moved house, like getting a new pair of shoes to match a new dress.) I didn’t know what she was complaining about—her parents were pretty cool in a carpool-and-curfew kind of way. But they were never enough for Amelia, who wanted them to be a part of the Hollywood side of LA. She had dreams of being a big star, and her parents (both of them English teachers) didn’t want her to hit the firmament until she finished high school and college.

“Well,” she said to me now, “if I had a few million dollars, I’d definitely give you a show to run. And I’d watch it every single day, if I wasn’t out on auditions.”

“Oh, don’t worry,” I told her. “If I have a show of my own, you’ll get to be the lead. There’s no way I could do it without you.”

She cheered around that, and we moved on to other topics—boys, classes, blah blah blah. The whole show idea would’ve probably ended there.

But then I got the next call.

It was Donald, my mother’s agent. He’d been my mother’s agent for as long as anyone could remember and was, as far as I could tell, the only straight guy who’d survived knowing my mother for that long without being eaten by her praying-mantis side.

“Hello, Mallory,” he said. Unlike most people in LA, he always said hello.

“Hi, Donald. What’s up?”

“I saw your blog.” He sa

id the word blog as if it was something out of a science-fiction movie. “I love your idea. Do you have a bible?”

Now, if I hadn’t grown up on a soap-opera set, this question probably would have thrown me—was Donald going to ask me to repent for my sins? Go check the Testaments to find some inspiration there?

But he wasn’t talking about the Bible. He was talking about a bible. Every show had one—the list of characters and plots and relationships and settings that acted as the foundation for all the stories the writers came up with. The longer a show ran, the longer and more complicated its bible became. At the beginning, it was usually about fifty pages and had enough characters and story ideas for a year’s worth of episodes.

Right then, of course, my “bible” consisted of exactly one ranting blog entry. But I wasn’t about to tell Donald that.

“Yeah, I have a bible,” I said.

He paused to think. Ever since I was a little kid, I’d imagined that if thoughts could have sounds, Donald’s thoughts would be like ice cubes clinking in a glass. There was something cold about the way he processed things, but also something a little musical.

Finally, he said, “Can you send it to me tomorrow? It’s a long shot, but I think the network’s been looking for something like this. And I’m having lunch with Stu Eisenhorn.”

Stu Eisenhorn was the president of the network on which Good As Gold aired. As far as I could tell, he’d never been jilted by, entangled with, or enraptured by my mother. Which was a big plus.

“I can get it to you first thing,” I said.

“That’s my girl!” Donald replied. Then he wished me good night.

As if I was going to get any sleep. I figured I had about six hours to come up with an entire soap opera.

The first thing I needed was a town name. The first word that came to mind was Deception, for obvious reasons.

That sounded like a start.

Deception …

I needed another noun.

Deception Mountain.

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!