- Home

- David Levithan

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) Read online

ALSO BY DAVID LEVITHAN

Boy Meets Boy

The Realm of Possibility

Are We There Yet?

The Full Spectrum (edited with Billy Merrell)

Marly’s Ghost (illustrated by Brian Selznick)

Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist (written with Rachel Cohn)

Wide Awake

Naomi and Ely’s No Kiss List (written with Rachel Cohn)

How They Met, and Other Stories

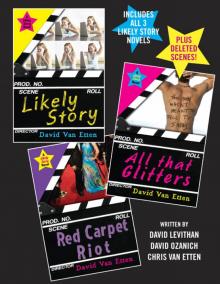

The Likely Story series (written as David Van Etten, with David Ozanich and Chris Van Etten)

Love Is the Higher Law

Will Grayson, Will Grayson (written with John Green)

Dash & Lily’s Book of Dares (written with Rachel Cohn)

The Lover’s Dictionary

Every You, Every Me (with photographs by Jonathan Farmer)

Every Day

Invisibility (written with Andrea Cremer)

Two Boys Kissing

Another Day

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

You Know Me Well (written with Nina LaCour)

The Twelve Days of Dash & Lily (written with Rachel Cohn)

Sam & Ilsa’s Last Hurrah (written with Rachel Cohn)

Someday

Mind the Gap, Dash & Lily (written with Rachel Cohn)

this is a borzoi book published by alfred a. knopf

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2021 by David Levithan

Cover art copyright © 2021 by Jill De Haan

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 9781984848598 (trade) — ISBN 9781984848604 (lib. bdg.) — ebook ISBN 9781984848611 — ISBN 9780593377444 (intl. tr. pbk.)

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

Penguin Random House LLC supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to publish books for every reader.

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Also by David Levithan

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Acknowledgments

About the Author

For Ben Lindsay, dear friend

1

They looked everywhere.

The woods behind our backyard. The school. The woods behind the school. The basement. The attic. The pond, even though the pond was a long walk away. They called the parents of every kid in Aidan’s class, even the ones who’d moved away.

We opened every door to every room in our house, every door to every closet. We searched every crawl space, checked under every bed. We pulled back each of the shower curtains and looked for footprints in all of the rugs. It was a game of hide and seek that got old after five minutes, alarming after an hour, and the scariest thing that had ever happened to any of us after that.

Aidan couldn’t be found.

* * *

—

They asked me the same questions over and over again.

When did you last see him?

I was falling asleep. It was his turn to shut off the lights. I saw him get out of his bed and go to the light switch. Then I heard him get back into bed, and I think we said goodnight.

What time was this?

Around ten?

You’re not sure.

That’s usually when we turn out the lights. I wasn’t paying attention. I just wanted to go to bed.

Were you asleep when he left the room?

I think so. I didn’t hear the door.

How long does it take you to go to sleep?

I don’t know.

Does your brother usually get up in the middle of the night?

I don’t think so.

Have you ever caught him sleepwalking?

No.

Did he say anything to you about running away?

No.

Do you think he ran away?

Only because he’s not here. But there’s no reason for him to run away. He’s twelve.

And you’re eleven, Lucas?

Yes.

He didn’t say anything unusual to you?

No.

He wasn’t mad about anything?

No. And if he was really running away…

What?

He would have taken his phone. He wouldn’t have left it behind. He loves his games too much.

Is there any place your brother would have gone? Any friends he would have wanted to see?

Late at night? No.

No one.

Glenn’s his best friend. But he sees Glenn all the time. I mean, during the day. I don’t think they would meet up at night in secret, if that’s what you’re asking. But I guess you’d have to ask Glenn.

Is there any place your brother goes to hide? Like when you’re playing—where does he hide?

The attic. Aidan always hides

in the attic.

* * *

—

They checked every inch of the attic. They moved every box, opened every old cupboard, chest, and dresser. There were traces of Aidan up there—footsteps and fingerprints left in the dust. But there were traces of Aidan everywhere. This was our house. We lived all over it.

They looked for a note. They looked at the histories of every device Aidan used. They looked in a circle around our house, trying to find a trail. And they also looked for any sign that someone had broken in and stolen him away from us.

So much looking. And they couldn’t find a thing.

* * *

—

Did you get into a fight with Aidan?

No.

Did your parents get into a fight with Aidan?

No.

Did you yell at him?

No.

Did they yell at him?

No.

Was there any reason for him to leave?

No.

Are you sure?

Yes.

* * *

—

Neighbors and strangers banded together to search, walking at arm’s length through fields and forests, staring at the ground for clues. The pond—they kept coming back to the pond, even though I told them we never went near the pond, because it was on Mr. Magruder’s property, and Mr. Magruder had told us to stay away. Even Aidan, who was much braver than I was, or maybe much more reckless than I was, wouldn’t go near the pond.

They listened to me, but not really.

An alert was sent out. It was on the news. Reporters asked the people watching to call the number below if they had any information.

Lots of people called, but nobody had any information.

* * *

—

Were the two of you close?

I thought we were. I’m not sure.

* * *

—

We’d always shared a room. For as long as I could remember, sleep meant the two of us breathing the same air, our eyes adjusting to the same darkness. I’d grown used to just about any noise he could make, although there were definitely times I woke up to hear him talking to himself and was surprised by what he was saying. (One time I heard him say “Good job!” and assumed he was complimenting me on my own sleeping.) His snoring could be thunderous—but he said the same thing about my farting.

I knew him. I knew his favorite foods. I knew his least-favorite baseball team. I knew which socks he’d choose to go with which shirt and exactly which grunt he’d make when he felt the game he was playing had cheated him out of a win. We were one year apart, and most of the time people thought I was the older one, even though I wasn’t. I paid attention to him, but I didn’t pay enough attention to know for sure whether he was paying any attention back.

And, of course, when my attention was needed the most, I failed. I was asleep.

Good job.

* * *

—

Our town wasn’t very big, but it seemed much bigger when you were considering all the spaces a twelve-year-old could disappear into. Not just the pond, but the trees. Not just the trees, but the fields. Not just the fields, but the sewers. Not just the sewers, but the houses. Not just the houses, but the stores. The trash cans behind the stores. The cars left unlocked.

Hide and seek.

None of his friends had seen him or talked to him or had any idea where he was. Glenn and his parents came over to our house, but all they could do was feel helpless alongside us. The police asked Glenn if they could talk to him, the same way they’d asked me. As if we had a choice. Of course we talked to them. Of course we were willing to tell them everything we knew. I assumed they asked Glenn the same questions they asked me, or mostly the same questions. But never at the same time. Whenever Glenn’s phone lit up with a text, they asked if it was Aidan. But it was always another friend, wondering what was going on.

I had a phone, but I was only supposed to use it for emergencies. This was an emergency, but the only person I wanted to call about it didn’t have his phone.

We kept watch. There was always someone awake. Just in case there was a call. Just in case there was a knock at the door.

We made sure the doors were locked, fearing intruders. You had to knock or ring the doorbell for someone to let you in.

That ended up being important.

* * *

—

Are you sure you can’t think of anything else?

* * *

—

One day turned into two days.

Two days turned into three days.

I didn’t go to school. Mom and Dad didn’t go to work. Mom tore at napkins and paper cups. When she was through, she would look at her lap as if the pieces had fallen there from the sky. Dad kept searching, even if it was in the same places that had been searched a hundred times before by a hundred different people. “We have to be missing something,” he kept telling us, and finally Mom shut him up by saying sharply, “It’s Aidan, Jim. We’re missing Aidan.”

People kept coming by. They put up signs everywhere.

Missing. That word again.

I didn’t know whether it described what Aidan was or how we felt.

He was missing, and it felt like every word we spoke, every move we made, every thought we had was an act of missing him.

* * *

—

Think, Lucas. Think hard.

* * *

—

Glenn asked me if I wanted to go over to his house, to play some games. I didn’t think it was his idea. I didn’t want to leave, but the fact that I didn’t want to leave made people think I should get out of the house.

“It’ll take your mind off things,” Dad said.

What he meant was that it would take their minds off of me for a second. So I went. Glenn tried to get me to play all the games Aidan would play, the ones Aidan was good at. I sucked at them because he always beat me and I always gave up. Now I was playing Aidan’s games with Aidan’s best friend in Aidan’s best friend’s house and that didn’t take my mind off things at all.

“You have no idea where he is?” Glenn asked as he doused Nazis with a flamethrower.

“No,” I said, not taking my eyes from the screen. “You?”

Glenn just shook his head, killed more Nazis.

When I told Glenn’s mom I wanted to go back home, Glenn didn’t look either disappointed or surprised.

I’d never been as much fun as my brother.

* * *

—

Three days turned into four days. Four days turned into five.

They wanted to dredge the pond. What if he’d fallen in? What if that was why they couldn’t find him?

I noticed the difference: They weren’t talking about finding Aidan. They were talking about finding Aidan’s body.

My parents didn’t want to hear this. When Aunt Brandi called from her vacation in Peru and told my mother she was coming home because they had to start preparing for the worst, Mom told her not to say another word, that nobody was going to talk about Aidan as if he was anything other than alive. He was missing. That’s all.

I didn’t think he was dead. I felt that if he were dead, I would know. The same way I’d know if one of my arms was missing or if my house had burned down. I said it to myself, “He’s not dead. I know he’s not dead.” I made sure no one else was around when I did this.

Mom has family pictures in every room of our house. I kept looking at Aidan’s face in those pictures, kept asking him where he was. I was scared that he’d be frozen in those photos forever, never getting any older.

I didn’t sleep much. I listened for any sign, any signal.

I felt guilty whenever I fell asleep.

When I woke up, the

re were only about five seconds when I was okay, when it felt like morning on a school day. Then I’d remember what was happening, and all the fear would descend.

You’re not dead, I said to him in my mind.

Then I waited for a reply.

* * *

—

The fifth day turned into a sixth day. The sixth day turned into a sixth night.

They expected me to go to sleep. Sleep: the scene of the crime.

Our house is two stories and an attic. Mom and Dad and some other people were downstairs. When I went to bed, everyone was trying to convince Mom to go to bed too, but she wouldn’t listen. She was still down there.

I was upstairs, kept awake by every single time I’d wished to have my own room, so I wouldn’t have to share one with Aidan. This is not how I want to get it, I told the universe, but the only response I got was from Bentley, Aidan’s old teddy bear, who Mom had taken from the shelf and put back on his bed.

Bentley stared at me, as if he was telling me, This is all your fault.

I heard something fall. Above me. In the attic.

I don’t know why I didn’t call for my parents. I don’t know why I didn’t run downstairs.

I told myself it was the wind. A raccoon. A ghost.

But I had to know for sure.

So I walked to the end of the hall. I opened the door that’s smaller than all the other doors, bent my head a little to squeeze through, and walked up the stairs.

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!