- Home

- David Levithan

The Full Spectrum Page 12

The Full Spectrum Read online

Page 12

In elementary school, I experienced difficulty in fitting in with my classmates. I don't believe I had a hard time making friends, per se. I got along with most people, but didn't have that one group of close friends that most kids have growing up. When you think about those early friendships, they are almost always based on chance occurrences—your parents are friends, or you live in the same neighborhood. But for me those childhood friendships seemed to disintegrate when chance occurrences didn't translate into commonalities beyond geography and parental acquaintanceship.

Sunday evenings were awful times for me while attending elementary school. My family would spend them with my grandparents, eating together, playing games together, watching made-for-TV movies together. That togetherness, in stark contrast with my lack of close friends, made the idea of starting another week of school unbearable. I sank into something of a childhood depression. I was lonely, but not because others weren't there to eat lunch with and talk on the playground with. I was lonely like a foreigner who's away from home—who longs to see someone who resembles them.

I began meeting with a counselor. While I enjoyed having someone to confide in, I felt that the therapist violated my confidence by discussing our sessions with my parents. I don't know for a fact this occurred, but certain things they would say and do seemed to be the logical result of the funneling of information from my counselor. The other thing I noticed about therapy is that, while it made me feel better (if for no other reason than verbalizing internalized frustrations), it didn't alleviate the outward problems. The feelings of isolation didn't disperse that easily.

Throughout counseling, I sensed tension building between me and my parents. They were always supportive, but as with most parents unknowingly raising gay children, they couldn't begin to understand or comprehend the emotions of my young mind. I sensed their frustration in attempting to understand, and that alone made me try to hide my problems from them.

In addition, it was all too obvious to my fellow students that I was going to counseling. That indicated there was something wrong with me. And as anyone who has ever worked with children will tell you, they have a keen ability to sense and exploit weakness.

I was at something of a standstill. While the problems had not gone away, I could no longer discuss them with my therapist because doing so would alert my classmates there was something wrong, as well as my parents, who appeared to be as affected by what troubled me as I was. So began a process of bottling up all the crap life threw in my general direction.

It's interesting when you think about it, the idea of holding things inside. Part of me marvels at how strong I must have been—a kid holding back his pain to spare his parents the frustration of having a son who for one reason or another can't fit in. But on the other hand, I suppose I was weak, or at least too weak to deal with things as they happened. Either way, the decision to keep it all inside was an unhealthy one. I've always marveled at those individuals who are able to keep things to themselves—not in order to hide them, but just in order to live a more private life. I guess I'm just not good at keeping things private—or at least not major things. As much as I tried to restrain myself from letting the world get me down enough to let it show, it did.

In middle school, I remember wondering how I was ever going to survive the experience. I certainly never expected I would ever be sharing my story with others—who else would care to listen? Who else could possibly understand the turmoil that I tried to ignore, all the while being beaten by the reality that I couldn't escape it?

I doubt a single day went by without someone calling me a fag, or threatening to hit me, or actually doing so. Somehow I managed to make it through middle school without sustaining any visible wounds, but the ones that went unseen likely hurt more. When these kids taunted me with anti-gay epithets, I knew instinctively they were right. How they could possibly know my most intimate secret, I couldn't fathom. At this point in my life, being gay simply meant having the occasional thought about other boys. As I hadn't acted on those feelings, it baffled me how anyone could be observant enough to notice.

Growing up completely isolated from any positive gay role models, I never considered coming out. Instead, I contemplated ways to prove the bullies wrong. But how can you prove to someone you're not gay? I later read somewhere, “ ‘Straight’ always has the possibility of being in the closet.”∗ Had I known that at the time, I suppose it would have empowered me. Still, as much as I may fantasize that being openly gay would have disarmed the bullies—my reclamation of words like “fag” and “homo” leaving them unarmed—it is likely far from the truth. I wonder how much time and energy I spent dreaming up ways to make those insecure little boys believe I was straight. I dated girls, but that didn't stop the name-calling. Sometimes when I happen to run into exgirlfriends of mine, I feel the need to either apologize or thank them for being there for me at an absurdly difficult time. Without knowing it, they made life a little bit easier. Even though the other boys didn't stop harassing me, these girls gave me something to throw back in their faces. And while one could make the assumption I was simply using these girls, I believe they needed me as much as I needed them. Middle school is a tragic time for us all, and as we held hands at school dances, the skeletons in our closets were able to tango without too many people noticing.

I vividly remember one individual who seemed to exist for no other reason than to make my childhood a living gay hell. On nearly a daily basis, he would stand up in class, in front of my home economics teacher, and announce to the students that I was gay. He yelled it down the hall between classes, yelled it in the

∗Benjie Nycum and Michael Glatze, XY Survival Guide (San Francisco: XY Publishing, 2000).

locker room before gym class, and yelled it in my face one night while he and a friend of his took a few swings at me.

When I reported the harassment to a school official, I suddenly found myself in the office of one of the school counselors. The counselor never asked me if I was gay. He assumed I wasn't. It's funny, the majority of kids assumed I was, and the majority of adults—including my parents—assumed I wasn't. The school official gave me tips on how to walk, talk, and appear more masculine. This, he assured me, would prove to them I was not gay. What a wonderful lesson to teach a young person: If someone makes fun of you for being different, try your hardest to act just like them, so they'll see you're just the same. What happened to everyone being unique?

I will always harbor some resentment to the gentleman who thought it easier for me to change who I was than to solve the real problem of intolerance and homophobia in the halls of my school. But life is too short to hold too much of a grudge. I ultimately forgave the bully who taunted me—I later learned he was just as gay as I was. And I hereby forgive Mr. Elshere for never asking me the most obvious question, “Are you gay?”

I forgive him mostly because I'm not sure I would have answered honestly. And even though I believe I deserved the option, I can't expect people to think in a way they may never have been forced to think before. I only hope that the children of Watertown Middle School are no longer assumed to be anything but individuals who deserve to be themselves, to walk their own walk, talk their own talk, and be as masculine or feminine as God made them.

Oh, I almost forgot about God. In the midst of middle school, there was another force at work. Having grown up in the Wisconsin Synod Lutheran Church, I was making my way through two years of confirmation at the same time I was starting to realize I was gay. Growing up gay is a series of baby steps—knowing it, realizing it, acknowledging it, living it. And I was still just beginning the journey.

Spiritually, I always took the teachings I learned in Sunday school to heart. The fact was, Christianity made sense to me. You could attribute that to the fact I grew up in a Christian household, but I think the basic concepts of forgiveness, unconditional love, and striving to avoid temptation were what made sense. Now the problems with Christianity were about to unfold in front of me. See, Christians like t

o construct implausible expectations of how everyone around them should live their lives. Then, at least in my church, they attempt to deceive the rest of the congregation into believing they must meet those unattainable standards of heavenly perfection. Sermons in my church seemed to damn people to hell for the most ridiculous reasons—divorce, marriage outside the church, worshiping in a different and therefore wrong way. How awful it must have been for churchgoers who fell into those categories to listen to such an ungodly message. Before long, I found myself falling into the worst category of all. I wasn't just a sinner, I was an abomination.

Religion was something of a mystery to me. I think that's because the church that I grew up in tended to imbue religiosity with a sort of smoke-and-mirrors ambiguity with regard to logic and reason. Congregants were expected to believe wholeheartedly, and were discouraged from questioning. Like a parent with no answers, the pastors I grew up with expected me to be content with “Because it says so in the Bible” as the answer to some of the most important questions I was asking. The source of infinite wisdom, the Bible, was selectively utilized—some passages set in stone, while others were unimportant or dismissed when they inconveniently threw a wrench into the aforementioned illogicality.

Why, for instance, if homosexuality inevitably results in damnation, did it not make God's Top Ten list? And why, if homosexual intercourse trumps all other sins, does the Bible clearly state that no sin carries any more weight than another? And if I was wrong, and they were right, and being gay was a sin, then why didn't Christ forgive that sin—like he promised to forgive all the others?

For many years after that, and still in some ways to this day, I turned away from organized religion. I personally believe that the road to one's own spirituality should be a journey, not a roadmap handed to you by your parents that you blindly traverse. If it weren't for my frustration with my church, I may have never found my own personal relationship with the spiritual side of myself—a relationship I am still courting.

Despite the chaos of those two years of religious indoctrination, I survived—sanity intact—and began high school ready to start anew and reinvent myself. I don't know if I had a particular grasp on who I was in middle school, but I knew I didn't want to be that person anymore. I wanted to find my own voice, even if I wasn't quite ready to use it.

I began competitive speech, an activity I seemed to have a talent for. I made friends and began to build a reputation for myself— aside from simply being the kid everyone thought was gay. In fact, the anti-gay epithets seemed to decrease—or maybe I was just too busy to notice them. Either way, life improved. And for a moment, I thought just maybe I would never have to face the difference I felt.

I don't need to go into the details of my first homosexual experiences; doing so would out individuals who may or may not appreciate my openness. Suffice to say that high school opened doors for me—doors that I didn't entirely understand.

I remember the first real sexual encounter I had as a young man. For years I blamed that particular individual for making me gay, as ridiculous as I now know that to be. The relatively innocent experience made me sick by how dirty and wrong I felt afterward, and for many years, I wondered if those negative feelings meant that being gay was wrong. Hindsight seems to lend credence to the fact that the negative feelings were a combination of disappointment and fear as I began the lengthy and confusing process of shedding society's expectations and creating the me I was born to be.

In a way, my high school busyness was just a diversion. It left me little time to worry about what other classmates were saying about me, both behind my back and to my face. But as with any diversion, I soon realized that the problems I was trying to escape from didn't go away. Luckily, instead of losing myself in drugs or alcohol, I was losing myself in activities like speech, debate, theater, and student organizations. After three long years of working to establish a name for myself other than “faggot,” I began to realize that no matter what sort of reputation I earned for myself, being gay would always be a part of it—and the sooner I could accept myself, the sooner other people would be given the chance to wholly accept me as well.

The relationships I cultivated in high school were tenuous at best. I always wondered if the friends I had would still be my friends if they knew my secret. So while I was outwardly surrounded by friends and acquaintances, I couldn't help feeling lonely. Despite the progress I had made, not much had changed since elementary school.

But one thing had changed. The journey, even though not yet finished, had armed me with tools I would later use to defend myself. Having to stand up for myself in my conservative Midwestern hometown had taught me how to stand up for myself, and that lesson proved to be an invaluable one.

I will never forget the first time I actually came out to myself. My senior year in high school, I traveled to various parts of the country speaking on the issue of gender roles and individuality. In the speech, I made an untrue confession. “I'm not a homosexual, I just don't fit the standard,” I said, in reference to the rigidity of gender stereotypes. Sometimes I look back and fault myself for not having the strength to come out in high school. Surely I would have opened minds and helped my sleepy little town wake up to the fact that gay people are not so different from the rest of society. But it wasn't that easy. I spent weeks in Internet chat rooms, typing away about my problems to nameless, faceless strangers who offered some degree of comfort. A pen pal provided solace as we both came to grips with our sexuality simultaneously. And one evening, alone in my room, I said it aloud—almost as a way of testing myself to see if I could really do it. I'm not sure what I expected to happen. I think part of me honestly believed that verbalizing this internalized part of me would somehow stop time in its tracks— and, in a way, I suppose it did. At first I said it quietly. Then again, and again, louder and louder, until my face was awash in tears, and the words “I'm gay” were barely audible beneath the sobbing. The world didn't stop turning. The experience was both empowering and terrifying. I had finally taken the first and most important step in accepting myself—and accepting my path unconditionally. Now that I had, in effect, admitted what I had known to be true for so long, there was no turning back. The path ahead looked dangerous and difficult—definitely the road less traveled. But I suddenly realized I was stronger than I had ever given myself credit for. And as I sat there, alone in my room, drying my tears, I was both proud and ashamed of that strength.

While saying it aloud to myself was the first step in coming out, it was only the beginning. Moving away to college, I again had the opportunity, as I did in high school, to reinvent myself. I spent a lot of time deciding whether or not to reinvent myself as loudly and proudly gay, or if I should continue to hide my secret and attempt to maintain the lie I had been living.

One evening, I had the good fortune to hear Archbishop Desmond Tutu speak to an arena full of students and faculty at my small private liberal arts college in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Toward the end of the presentation, Tutu allowed for a brief question-and-answer period. One student stood up and addressed the archbishop. She noted the work he had done in his own country of South Africa to address the issue of gay and lesbian equality, and asked, “Isn't that contradictory to what the Bible has to say about homosexuality?”

The archbishop paused for what seemed like an eternity. I remember naively thinking that his answer would change the world—either opening up the hearts and minds of the audience members, or forever slamming the door on my neatly appointed closet. Then he started to laugh. “The Bible says a lot of things I hope you don't believe,” he chuckled.

That evening, empowered by the archbishop's message, I came out to my best friend. I hope that someday I am able to thank Archbishop Desmond Tutu for the strength it must have taken to live his life in such a way that led him to that auditorium to deliver his message of acceptance, tolerance, and unconditional love.

Later that year, I came out to my sister in an airport before I boarded

a plane for Germany. “I love you,” I told her. “I love you, too,” she said, somewhat surprised by my statement. “Well, then, there's something I should tell you.” “Okay …,” she responded. I hugged her as I said my next few words, partly because I was shaking so hard I needed her support to stand, and partly because I wasn't sure I could look her in the eyes for fear she'd turn away. “I'm seeing someone,” I said. “His name is Nolan.”

She hugged me back and said, “I am so proud of you.”

There are moments in life when no matter how strong you are, you feel too weak to keep yourself from falling. Some people describe those moments as feeling like the weight has been lifted from their shoulders. But I had been carrying that weight for so long, and the burden was so heavy, that I nearly collapsed when it was removed from me. My sister's support, both physically and spiritually, held me up, and continued to support me, encourage me, and love me unconditionally.

The next step out of the closet was the most difficult. Several months later, a familiar scene played out. Again at an airport, this time in Atlanta, moments before boarding a plane for Ireland, I stood, trembling as before, as I held a letter I had written to my parents. My friend Keryn, whom I came out to after the arch-bishop's speech, held me as I dropped it into the post office slot, addressed to my mom and dad. I cannot begin to put into words the range of emotions that flooded my body as that letter left my fingertips and became lodged in the mail slot, forcing me to once again summon the strength it took to make the impossibly difficult decision to mail my coming-out letter.

I will forever cherish these difficult moments, both for the intensity of the experiences and the unbelievable strength they demanded of me. We've all read about moments of tragedy where people are able to summon superhuman strength, lifting cars off of victims trapped below, or racing into burning buildings to rescue those inside. These moments of greatness astound others, who wonder how otherwise normal individuals were able to do such unbelievable things. And while some may disagree with the comparison, these coming-out experiences were my moments of greatness.

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

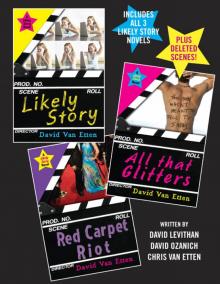

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!