- Home

- David Levithan

How They Met and Other Stories Page 16

How They Met and Other Stories Read online

Page 16

Now it was just us, so we spent most of dinner talking about everyone else. Because that, in essence, was what we had in common: our friends, our classes. And also the confusions we tried to hide, the pressures we tried to resist. We loved the same movies—dark, twisted comedies with semi-sentimental endings. We each read the newspaper in the morning. We wanted our emotions to read like poetry, even if the poetry we wrote never managed to read like poetry, because we never really figured out how to put the emotions there.

She wasn’t pretty, but there were moments when I found her beautiful. I was just starting to figure these things out. I liked her breasts, I liked her smile…and I loved her eyes. They had at least five colors in them, but I could never tell exactly which ones. As we gossiped over grilled cheese, I rubbed my bare ankle against hers. Not to be provocative or possessive. Just because it felt good to have that spot on me touch that spot on her.

We ate fast, like we always did. It was still light out at eight, so we drove over to my mom’s house and hung out there for a little. I don’t think my mom even knew it was prom night; she was simply home on a Saturday night like she always was, with her son and her temporarily adopted daughter swinging by to keep her company for the space of a TV show. By the time the credits were rolling, dusk had settled outside the window, and we were ready to go.

We had spent the last week planning this, not telling anyone for fear that they’d want to join us. With the group, any set of plans was also an invitation.

Now the rest of the group was safe in a Sheraton, wondering where we were, but not for too long. As we drove through the newly settling night, Kelly and I pieced together what we knew about what they were wearing, who they were sitting with. We placed bets on who would be the king and queen. We cast our own votes.

We got to the soccer field about ten minutes later. It was behind our old middle school, with a parking area all to itself, sheltered from view. I parked the car, turned off the headlights, and the two of us took the bags out of the backseat. These were the true fruits of our planning—our way of imprinting ourselves onto the evening, without having to wear a gown or a tuxedo.

We walked up to one of the goals—metal-framed and orange-netted. Kelly took out a string of paper lanterns from one of the bags. Neither of us was tall enough to hang them on the goalpost, so I had to lift her onto my shoulders. Then I lit candles and handed them up to her, trying to cup the flames as I did. When we were done, it looked like something strung out from a haphazard luau. But we loved it because it was peculiar. It wasn’t what we thought it would be, but we were used to that.

There was a streetlamp perched over the field, even though there was no street in sight. By its light, we unpacked the rest of the bags—blankets, cheese and bread, more candles, music player and speakers, chocolate. We were intellectual virgins, so instead of bringing contraceptives, we brought books of Margaret Atwood’s poetry and Sylvia Plath’s prose. And at first we read to each other, by that mix of candle and streetlamp—not just from the books, but from notebooks and Xeroxes, our own observations matched with the observations we wanted to make our own.

Then we lay back, rolling up unneeded sweaters under our heads, leaning into each other for light touches and deeper holding. We talked about everything that was about to happen—graduation, the summer, college—without talking about what would happen to us. We kissed, groped. The night stayed warm. Then we stared up at the sky, searching for the stars that weren’t quite there. We started to narrate a prom of our own making, taking it for granted that we were both picturing the same things as we said them.

“Right now, Alison Shaw is slapping Aiden across the face with her bouquet, because Samantha finally told Alison about her and Aiden hooking up.”

“Poor Cynthia is sitting at the table, afraid to dance.”

“Brett has to be drunk by now, so he’s singing along loudly to the wrong song.”

“Jeanette and Jeremy are dancing together, and they don’t realize anyone else is in the room.”

“Whoa—I think Brett just puked.”

“But Jeanette and Jeremy didn’t even notice.”

Then we went quiet, slowing the world down to the pace of our breathing. We fell into a trance of almost-sleep, shifting softly, touching in murmurs. We, too, could feel like we were the only ones. We lost track of time because we felt like time had lost track of us. Months from now, our relationship wouldn’t break up so much as dissolve. But here was the opposite kind of dissolution—that evaporation into a common moment, far from nothing and also far from anything else.

It was Kelly who looked at her watch, who realized it was almost midnight, the end of the prom. She jostled me up, and I reached past the still-wrapped food for the music. I pressed play…and nothing happened. Kelly took the player from me and looked at the blank screen.

“You have a charger in your car?” she asked.

And I said, “No…but I have a car.”

The candles in the paper lanterns had long since burned out, so now they hung like grown-up balloons from the goalpost. I watched them stir as I walked past. Turning the car on, I woke up the radio and cranked the volume as loud as it could go without waking the neighborhood. Then I left the door wide open, the inside of the car dimly gathering light from its small plastic chandelier. By the time I got back to Kelly, a song was just starting.

“Well done,” she said.

We held each other as the song started to play. I don’t want to say what song it was; that, more than anything, remains ours. It’s not really a song you can dance to—it’s a song meant for holding on. The temptation might have been to hold tightly, to pull each other so close that there was no distance, nothing between us. But instead we held lightly, so we could see each other, so we could look at each other’s faces and live in each other’s thoughts as well as our own. In my car, radio waves were being translated into sound, carrying across air, translating back into this loose communion, this song shared.

Did I love her then? Yes, in a genuine way. But I knew it wasn’t everlasting, and that was okay. We had the time that we had, and we would be together for the rest of it.

I think I want to leave us there. I want to leave us in that corner of the middle-school soccer field, lit by a streetless streetlamp, listening to our prom song pour out from an old Buick. Let’s stay on this song, before it turns to something else, before it switches to a commercial. Let me hold on to this the way it was, before I knew anything else.

A ROMANTIC INCLINATION

Their eyes met across the room, at an approximate inclination of twenty degrees.

Sallie gazed at James.

James gazed at Sallie.

And at once, both were illuminated.

Through the convex lenses of his glasses, James stared at the beautiful mass of matter named Sallie Brown. She seemed larger than life (a magnification of forty-nine times, to be precise). There she was, thoughts diffusing into her notebook, paying attention to the lecture that he could not bear.

Her magnetism was something he could not resist. He just kept exerting energy in her direction, stealing a glance once every 6.6 seconds. His heart grew in volume and defied gravity at the very sight of her, with her vibrant sense of humor and radiant personality providing other coefficients of attraction. Sometimes, her smile would raise his body temperature two Celsius degrees.

James Helprin was very much in love, for that millisecond.

And so, to add symmetry to our story, was Sallie Brown. Her attraction toward James was not just one of surface value—she liked his inside parameters as much as his outside exponents. The thought of him with her made her head spin like an unbalanced torque and made her heart slide like a kilogram weight on a frictionless pulley.

Sallie Brown desired a romance of great intensity, one that would relieve her from the pressures of her daily life. She needed a buffer from collisions, a balance when her equilibrium was threatened.

And so, periodically, she looked ove

r at James, with James returning the glance with an equal and opposite magnitude at different periods.

Yet Sallie and James had both life and the laws of physics working against them. You see, Sallie Brown and James Helprin were good friends.

Which adds a certain friction to our equation.

The minute their eyes truly met, that fateful day in AP Physics class, both objects were unprepared for the introspection that followed.

Sallie, no stranger to loving, laughing, and losing, was immediately shocked by how serious she was about James. He had long been a constant to her, one that she often relied upon when there were too many unknowns in her life. Did she really want to send their friendship to infinity by liking him?

The crests of every relationship, Sallie figured, were always followed by troughs (and crests again, if you had the patience—which she didn’t). She imagined their attraction turning to repulsion, just like that between a pith ball and a like-charged rod.

My God, she thought. Would I polarize him?

She thought of all the work that it would take to maintain equilibrium. She had only so much potential energy to give.

Would it be enough?

Meanwhile, James was having thoughts parallel to Sallie’s. The look in her eyes had given him a shock. He started to wonder if their “going out” would reduce to zero everything they had. Friendship had long been the basic element of their relationship. Now, both of them contemplated change. Yes, as Lenz had observed, change can turn on the source that created it, creating a force opposite to the best intentions.

James knew that the road to a simple harmonic relationship would be a hard one to follow. The critical point could only be reached through the passing of three states, each one causing a change in speed and the refraction toward or away from the norm.

And James seriously doubted that he and Sallie had the chemistry—or, in this case, physics—to make it.

If it is to be assumed that Newton was correct (as is the general consensus), to every action there is always opposed an equal action. That is to say that love always goes against a certain gradient. Sometimes risk. Sometimes popular opinion. In this case, regret.

Yes, James feared that liking Sallie would lead him to regret. He would regret liking her in the first place. He would regret breaking off their friendship. He would regret it when, after the statistically assured breakup, they would avoid each other like oil and water.

James did not want Sallie’s and his friendship to consist of meetings between classes and periodic waves in the halls. He knew that if their lives had to revolve around each other, they’d grow bored (not to mention dizzy). The damage would be done—the recoil irreparable.

After the initial impulse, James wondered, would the momentum remain constant?

Sallie’s doubts were only reinforced by her textbook. It defined a “couple” as “two forces on a body of equal magnitude and opposite direction, having lines of action that are parallel but do not coincide.”

Would we ever intersect? she asked herself.

She feared fusion would only bring fission, with the mass deficits too great and the energy spent too consuming to make the romantic endeavor worthwhile.

James, having a larger surface and cross-sectional area than Sallie, was worried about the strain that would possibly put a damper on their combined molecular activity. He calculated that as the length of their involvement grew, so would the tensile strain.

He also feared the work that would be needed when he and Sallie wouldn’t be together. Using W = Fd as his guideline, James figured out the work that it would take to keep their relationship at a constant force when he and Sallie were more than a mile apart. Furthermore, if he wanted to reduce the force (and, therefore, the work), he would have to slow down love’s acceleration by massive proportions.

With a girl like Sallie, a constant velocity with little to no acceleration would not be acceptable (or so James thought).

And yet a velocity increase would require an energy increase. Energy that James would find hard to muster up in this, his hardest year in high school.

Even simple harmonic motion, that romantic-sounding phenomenon, said that acceleration was proportional to negative displacement, which was not an encouraging thought.

Would we lapse into inertia without constant acceleration, requiring a larger force? James asked himself.

Even batteries would be sources of potential difference, thought Sallie.

I don’t even know if she’s a conductor or an insulator of emotion, James realized.

Boyle’s law soon served as Sallie’s guide.

According to Boyle, if the velocity of their affair decreased, the pressure would increase proportionally. Sallie was not prepared for this. Her heart had only a certain capacity for crisis.

Finishing her calculations, Sallie finally computed that the stress and strain of a romantic bond with James would be merely a waste of power, damaging the caring she had for him in the past.

She did not want the universe’s ever-growing entropy to interfere with her love life.

And thus, James drifted out of the focus of Sallie Brown’s affections.

And, in an action so simultaneous that many scientific minds would have been baffled, James Helprin took Sallie out of his romantic-life equation. He knew the friction of a merging of their hearts wouldn’t be beneficial. It would be theoretically and realistically wrong.

The next time they found themselves looking at each other, James and Sallie both smiled.

In the end, friendship was proven to be the dominant force. The head and the heart were found to be the joint sources of true romance.

It has been demonstrated.

WHAT A SONG CAN DO

If I didn’t have music, I don’t know

if I could ever be truly happy.

Happiness is music to me. Like when

I am in Caleb’s room, playing

my guitar for him, watching him

close his eyes to listen and knowing

he understands what I am

singing. That is all I need

to make a room full of happiness—

two boys, one love, and a song.

I think the reason my parents wanted me

to play classical music was because

it didn’t have any words. They would keep me

as a sound, not a voice. But I had

other ideas. I blew off the recorder,

did not bow to the violin, benched the piano, saved

up for a guitar. Then I used it to write

love songs for boys, and sad songs for love.

I sang myself to find myself

in a language far from my parents’

expectations. I taught myself the strings,

the chords, the fretting. But I did not

have to teach myself the words.

They’d always been there, notes to myself,

waiting for the music to bring them out.

All I had to do was recognize the possible

music and the songs were everywhere.

It is not something I have control over,

no more than I can control the sights

that appear before my eyes. I will be staring off

in class, barely hearing the echo of

my teacher’s words, when suddenly

a verse will arrive free-form in my thoughts.

when I look out a window

I wish for you on the other side

even if you’re not there

I can see you in the clouds

As I transcribe the words in my notebook,

I can hear the sound of it in my head.

Many teachers have caught me strumming

an imaginary guitar, trying to find the chords

before they vanish with the next thought.

The first time I went out with Caleb,

this happened to me. We were talking

in the park, having a conversation that l

asted

the afternoon and the evening,

finding all of our common coincidences,

baring some of our unfortunate quirks.

At one point he went to get us sodas,

leaving me with my thoughts and the trees.

I was elated to have found someone

who could be both interested and interesting.

My thoughts revealed themselves

in the terms of a song.

you could be

the leaf that never falls from the tree

you could be

the sun that never leaves the sky

this might be

the happy ending without the ending

this might be

a reason to try

When he returned to me, he had two bottles

in his hands, and I was making furious leaps

into my notebook, playing the ghost guitar

and singing solos to the birds around me.

I apologized, embarrassed to be caught

showing myself so early, but he said

it was charming, then asked me if I needed time

to finish my refrain. Perhaps it was because he said

something so perfect, or perhaps it was because

the song made me brave, but I asked him

if he wanted to hear it, and when he said yes,

I sang to him, accompanied only by

the guitar in my head and the beat

of my heart. When I was done, there was

a moment of absolute silence, and I felt

like the ground had been pulled out from under me

and I was about to fall far. But then the ground

came back, as he told me it was wonderful,

as he asked me to sing it to him again.

It is a sad fact of our present times

that it’s nearly impossible to turn on the radio

and hear a gay boy with a guitar.

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

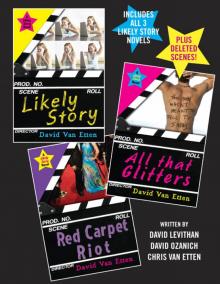

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!