- Home

- David Levithan

Someday Page 2

Someday Read online

Page 2

X

To stay in a body, you must take that body over.

To take a body over, you must kill the person inside.

It is not an easy thing to do, to assert your own self over the self that exists in the body, to smother it until it is no longer there. But it can be done.

I stare down at the body in the bed. It is rare for me to have done so much damage, so I’m fascinated by the result. The regular response to a dead body is to close its eyes, but I prefer them open. That way I can study what’s missing.

Here is the face I have seen in the mirror for the past few months. Anderson Poole, age fifty-eight. When I look into his eyes, they are only eyes, no more expressive than his dead fingers or his dead nose. The first time this happened, I thought there would be an aftercurrent of life—some element to enable the feeble and the desperate to believe that the spirit that had once been inside was now somewhere else, instead of completely annihilated. But all I see is utter emptiness.

There is no reason for me to be here. At any moment, the hotel management will overrule the DO NOT DISTURB sign and come in to find the reverend in a state far beyond disturbance. He died of natural causes, the inquest will conclude. His mind failed. The rest of the body followed.

Nobody will know I was here. Nobody will know that the mind failed because I cut the wires.

It was time to move on. I was getting bored. Anderson Poole was no longer useful.

I am in a younger body now. A college student who will not be attending class much longer. I feel stronger in this body. More attractive. I like that. Nobody ever looked at Anderson Poole as he walked down the street. It was his position as a reverend that they revered. That was the reason they listened to him.

“You came so close,” I say to him, my new hand closing his left eye, then opening it again. “You almost had him. But you scared him away.”

Poole does not respond; I am not expecting him to.

The phone rings. No doubt the front desk, giving him one last chance.

I have to go soon. I cannot be here when the maid finds him. Screams. Prays. Calls the police.

Nobody will mourn him. He has no family left. He had a few friends, but as I choked off his memories and made his decisions for him, the friends fell away. His death will cause no great disruption in anyone else’s life. I knew this from the start. I am not heartless, after all.

It is important for me to come back and see the body. I don’t have to, and sometimes I can’t. But I try. It’s not to pay respects. The body can’t accept any respects—it’s dead. By seeing what a body looks like without a life inside, I get a sense of what I am, what I bring.

I would like to compare notes on this with someone else like me. I want to sit down with him and discuss the act of being a life without being a body. I want to make my brethren understand the power we have, and how we can use that power. I want my history recorded in someone else’s thoughts.

Poor Anderson Poole. When I started with him, I learned everything there was to know about him. I used that. Then I dismantled it bit by bit. He no longer had his own memories—just the memories I had about him. Now that we are separate, I will make no effort to retain those memories. His life, for all practical purposes, will vanish.

Were I to thank him now, it would be for being so weak, so pliable. I take one last look in his eyes, witness their useless stare.

How vulnerable it makes you, to depend on a body.

How much better to never rely on any single one.

A

Day 6065

Life is harder when you have someone to miss.

I wake up in a suburb of Denver and feel like I am living in a suburb of my own life. The alarm goes off and I want to sleep.

But I have a responsibility. An obligation. So I get out of bed. I figure I am in the body and the life of a girl named Danielle. I get dressed. I try to avoid imagining what Rhiannon is doing. Two hours’ time difference. Two hours and a world away.

I have proven myself right, but in the wrong way. I always knew that connection was dangerous, that connection would drag me down, because connection is impossible for me in a lasting way. Yes, a line can be drawn between any two points…but not if one of the points disappears every day.

My only consolation is that it would have been worse if the connection had been given more time to take hold. It would have hurt more. I have to hope she’s happy, because if she’s happy, then my own unhappiness is worth it.

I never wanted to have these kinds of thoughts. I never wanted to look back in this way. Before, I was able to move on. Before, I did not feel that any part of me was left behind when the day was done. Before, I did not think of my life as being anywhere other than where I was at that given moment.

I try to focus on the lives I am in, the lives I am borrowing for a day. I try to lose myself in their to-do lists, their homework, their squabbles, their sleep.

It doesn’t work.

* * *

—

Danielle is taciturn today. She barely responds when her mother asks her questions on the way to school. She nods along to her friends, but if they were to stop and ask her what they’d just said, she’d be in trouble. Her best friend giggles when a certain boy passes, but Danielle (I) doesn’t (don’t) even bother to recall his name.

I walk through the halls. I try not to pay too much attention, try not to read the stories unfolding on the faces of the people around me, the poetry of their gestures and balladry of those who walk alone. It’s not that I find them boring. No, it’s the opposite—everyone is too interesting to me now, because I know more about how they feel, what it’s like to care about the life you’re in and the other people around you.

Two days ago, I stayed home and played a video game for most of the day. After about six hours, I had gotten to the top level. Once I reached the end of the game, I felt a momentary exhilaration. Then…a sadness. Because it was done now. I could go back to the start and try again. I could find things I’d missed the first time around. But it would still come to an end. I would still reach the point where I couldn’t go any further.

That is my life now. Replaying a game I feel I’ve already won, without any sense that it means anything anymore to get to the next levels. Killing time, so all I’m left with is time that’s dead.

I know Danielle does not deserve this. I am constantly apologizing to her as she stumbles through school, barely paying attention to what the teachers are saying. I rally in English class, when there’s a quiz on chapters seven through ten of Jane Eyre. I don’t want her to fail.

It’s hardest when I’m by a computer. Such a brutal portal. I know, if I wanted to, I could see Rhiannon at any time. I could reach Rhiannon at any time. Maybe not instantly, but eventually. I know the comfort I would take from her. But I also know that after a certain point, after I took and took and took, she wouldn’t have any comfort left. Any promise I made to her would be worthless, no matter how much of my own worth I put into it. Any attention she gave me would be a distraction from the reality of her life, not a reality in itself.

I can’t do that to her. I can’t string her along with hope. I will always change. I will always be impossible to love.

* * *

—

It’s not like there’s anyone I can talk to about this. It’s not like I can pull aside Danielle’s best friend—Hy, short for Hyacinth—and say, I’m not myself today…and this is why. I can’t pull back the curtain, because in terms of Danielle’s life, I am the curtain, the thing that is getting in the way.

I never used to wonder if I was the only one who lived like this. I never thought to look for others. I am just like you, Poole intimated. But I knew that even if he also moved from body to body, life to life, what he did within those bodies was not like what I chose to do. He wanted to draw me close, to tell me secrets. But I

didn’t want to hear them, not if they led to dereliction and damage.

That’s why I ran. To end things before I could ruin them.

I’ve been running ever since. Not in a geographical sense—I have stayed near Denver for almost a month. But I am always seeing myself in relation to the place I’m getting away from, not in relation to anywhere I’m going toward.

I am not going toward anything.

I just live.

* * *

—

After school, Danielle and her friends go downtown to shop. They’re not looking for anything in particular. It’s just something to do.

I follow along. If I’m asked my opinion, I give it, but in as noncommittal a way as possible. I tell Hy I’m sleepy. She says we should go to City of Saints, the local coffee shop. I have no way to tell her that I don’t particularly want to wake up right now.

When Rhiannon was in my life, everything was a rush. I think about driving to get coffee with her, driving to see her again, how scared I was that each day would be the last day she’d like me, and how excited I was when this didn’t prove to be true. I picture her kissing me hello, the welcome in her eyes.

I hear the scream as a hand grabs on to my shoulder and violently pulls me back. I realize that the scream was Danielle’s name, and the hand belongs to Hy, and the truck I was about to step in front of is honking as it pushes past. Hy is saying “Oh my God” over and over and one of Danielle’s other friends is saying “That was close” and a third friend is saying “Wow, I guess you really do need that coffee”—making a joke that nobody’s finding funny. Danielle’s heart is now, after the fact, pounding with fear.

“I’m so sorry,” I say. “I am so, so sorry.”

Hy tells me it’s alright, because she thinks I’m apologizing to her. But I’m not. I’m apologizing to Danielle once again.

I wasn’t paying attention.

I must always pay attention.

The other friends are calling Hy a hero. The light changes, and we cross the street. I’m still a little shaky. Hy puts her arm around me, tells me it’s okay. Everything’s fine.

“I’m buying your coffee,” I tell her.

She doesn’t argue with that.

* * *

—

The rest of the day, I stay present.

This is enough. Danielle’s friends and family don’t mind if she’s quiet, as long as they can feel she’s there. I listen to what they have to say. I try to store it away, and hope I’m storing it where Danielle will be able to find it. Hy thinks her crush on someone named France is getting out of control. Chaundra is inclined to agree. Holly is worried about her brother. Danielle’s mother is worried that her boss is on the way out. Danielle’s father is worried that the Broncos are going to screw up their season. Danielle’s sister is working on a project about lizards.

These people think Danielle is here. They think she is the one who is listening. I used to get satisfaction from playing my part well, never letting anyone realize I was, in fact, an actor. It didn’t occur to me that I would ever let anyone see beneath the act, that there would ever be someone who saw me as a me. Nobody did. Nobody until Rhiannon. Nobody since Rhiannon.

I am lost in here.

I am lost, and I can’t ignore the most dangerous question of all:

What if I want to be found?

A

Day 6076

I am woken one Saturday morning by a text:

On my way. You better be up.

I imagine that even when you sleep in the same bed night after night, in familiar sheets surrounded by familiar walls, there is still a profound dislocation at the moment of waking. You grasp first to figure out where you are, then reach for who you are. With me, this becomes confused. Where I am and who I am are essentially the same thing.

This morning I am Marco. I use his muscle memory to unlock his phone even as I’m figuring out his name. I am typing Just getting up. How long ’til you’re here? before I can figure out who Manny, the person I’m texting, is.

10 min. Didn’t you set your alarm? I told you to set your alarm!

Marco did not set his alarm. I never sleep through alarms.

Stop texting, I reply. Drive.

Shut up. At a light. Be ready in 9.

I try to wash away the mental fog in the shower, but I only get a partial clearing. Manny is Marco’s best friend. I can access memories of him from when he was tiny, so they must be lifelong friends. Today’s a big day for them—somehow I know it’s important to get up and get ready. But I’m not entirely sure why.

It’s 9:04—not that early. I can’t tell whether there are other people in the house, still asleep, or whether I’m the only one around. I don’t have time to check—I can see Manny’s car pulling up to the curb. He doesn’t honk. He just waits.

I wave through the window, find my wallet, and head out of my room, out the front door.

Manny laughs when I get in the car.

“What?” I ask.

“I swear to God, if you didn’t have me as your alarm, you’d miss your entire life. You got the money?”

Even though Marco’s wallet is in my pocket, I have a feeling the answer’s no. The mind is weird this way: Without knowing how much money is actually in the wallet, I know it’s not the amount Manny’s talking about.

“Shit,” I say.

Manny shakes his head. “I’m gonna start charging your parents for babysitting, you dumbass. Let’s try this again.”

“One sec,” I promise. Then I’m out of the car and back through the front door, which I forgot to lock behind me. When I get to Marco’s room, I’m momentarily stymied.

Where’s the money? I ask him.

And just like that, I know to look for the shoebox under the bed, where there’s a wad of cash waiting for me.

What’s this for? I ask again.

But this time, nada. Some personal facts are closer to the surface than others.

When I get back to the car, Manny pretends he’s been napping.

“I haven’t been gone that long,” I tell him.

“You, my friend, are lucky I worked an extra fifteen minutes of fuck-up time into the schedule. We’ve been waiting for months for this, man. Leave your dumbassery in the backyard, okay?”

Somehow Manny makes dumbassery a term of affection; he’s amused by my delays, not angered.

“So what have you been up to since the last time I saw you?” I ask. This is one of the many Careful Questions I have in my arsenal.

“Well, it’s been a fucking lonely ten hours, but somehow I made it through,” Manny replies. “I’m so excited for you to meet Heller after all the hype. The guy’s shit is for real, you know? I still can’t believe he’s doing us.”

“Unreal,” I say. “Completely unreal.”

“Ric’s gonna be floored. I mean, his cobra is the bomb, but what Heller’s gonna do to us is going to make that cobra look like a worm, amiright?”

“So right.”

I really need to get in the game here. Best friends are like family members when they talk—the shared-history shorthand is a beast for me to decode. I latch on where I can—in this case, I know Ric is Manny’s brother. And it isn’t much of a jump from there to recall the cobra tattoo on his arm, to know that’s what Manny is talking about. Which means, as I clue in, that Heller must be a tattoo artist. And Marco and Manny must be going for tattoos. Their first tattoos.

Now I understand why Manny is so excited. This is a big day for them.

I can see the narcotic effect the expectation is having on Manny; he’s smiling at what’s going to happen a short while from now, buzzing on the trajectory that leads from now to then.

“Have you decided which one yet?” he asks. Then he doesn’t give Marco any time to answer, saying, “No—wait

’til we get there. Surprise me.”

“That’s easy enough to do,” I tell him.

“Just DON’T WUSS OUT!” He punches me on the arm playfully. “I swear, the pain is going to be worth it. And I’ll be there the whole time. Whatever you do, stay in the chair, right?”

Is he saying this because he senses my own hesitation, or because of a history of hesitation on Marco’s part? I suspect it’s because of Marco, but I worry it’s because of me.

Manny talks some more about when Ric got his tattoo, and how he kept taking the bandage off to show it to everyone, and how it came so damn close to getting infected. In trying to get Marco to remember this, I see all kinds of other memories instead. Ric and Manny bringing me to the beach, Manny’s bathing suit a junior version of Ric’s. Me and Manny sitting on his front porch, waiting for his mom to get home, setting our Pokémon cards out, swapping the doubles. More recently: Manny kissing a girl at a party while another girl talked to me and tried to get my attention. Manny throwing chicken nuggets at me and me throwing them back, the same birthday lunch we’ve had for as long as Marco can remember. Whichever of us is the birthday boy always gets a Happy Meal.

I get caught up in the times they’ve had together, and Manny lets me get caught. I’m not sure how long we drive before we pull up to a house and Manny says, “This is it.”

I’ve never gotten a tattoo before. I was expecting the tattoo place to be a storefront in a strip mall, neon letters spelling out T-A-T-T-O-O. But this looks like a house where a family of five could live, complete with a side door, like one belonging to a dentist or a doctor with a home office. That’s where we’re headed.

“If anyone asks, you’re eighteen,” Manny tells me. “But no one’s going to ask.”

This only makes me more nervous. Manny knocks on the office door, and it’s opened by a guy who’s probably thirty and is covered by more than thirty tattoos—all these different people in weird poses being devoured by the landscape. He sees me staring at them and says, “Garden of Earthly Delights.”

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

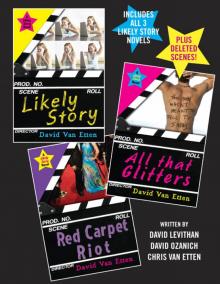

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!