- Home

- David Levithan

Are We There Yet? Page 4

Are We There Yet? Read online

Page 4

As they approach St. Mark's, the streets become more crowded. Danny weaves and bobs through the fray, dodging the men and women who walk at a more leisurely pace. Elijah follows in Danny's wake, without enough time to wonder if these couples are lovers, or if the children are playing games. Finally—too soon—they arrive at the Caffè Florian. Danny barks out their name and says,“Reservation, table for two.” The maitre d' smiles, and Elijah can sense him thinking to himself, American.

The restaurant unfolds like a house of mirrors—room after room, with Danny and Elijah stumbling through. Menus are procured, and the Silver brothers are shown to their table. Before he has even been seated, Danny orders wine and asks for some bread. Elijah studies his menu and wishes he knew more Italian.

The waiter is gorgeous—the kind of man, Elijah thinks, who would sweep Cal off her feet. It isn't just that he's beautiful but that his movements are beautiful. If all men looked like this waiter, there wouldn't be any need for color—just white shirts and black pants, black shoes and black ties.

Danny is more interested in the waiter's grasp of the English language (mercifully adequate). Even though Elijah is a vegetarian, Danny does not hesitate to order a rack of lamb. Elijah tries not to notice and orders penne. When it is pointed out to him that the pasta course is an appetizer, he assents to a grilled vegetable plate. The waiter seems pleased, and Elijah is pleased to have pleased him.

“So what are we going to do?” Danny asks, breaking off a piece of bread and searching for the butter.

Elijah is not sure how big this question is. He assumes it is a matter of itinerary, not relations.

“I'd like to go to the basilica,” he answers, “and the Academy.”

“Well, of course. Those are givens. But what else? And where's the butter?”

Elijah points to the dish of olive oil. Danny is not pleased.

“I'll never understand why people do that—olive oil is so far removed from butter. It's a totally different sensory experience, you know? It's like substituting salt for cheese. Doesn't make any sense.” Danny puts down the bread. “I'd like to go to the old Jewish ghetto tomorrow morning, if that's okay with you.”

Elijah is surprised. He had expected less of his brother—a search for the nearest Hard Rock Cafe, perhaps.

“We can go to the Academy when it opens,” Danny continues, “and then take a vaporetto to the ghetto. The whole Sunday thing shouldn't be a problem there.”

Elijah agrees, and is glad when the food comes—no need for further conversation. Which isn't to say the brothers don't talk. They do. But it's hardly conversation. Instead, it's filling the time with idle words—Danny returns to the topic of their parents' deception, and Elijah shifts gears by mentioning movies, one of the only things they can talk about easily. Even if Danny feels it's his masculine duty to disparage Merchant Ivory, at least it's something to talk about. Elijah realizes this strain in conversation now, and Danny has the same thought a few minutes later. But there is no way for the two of them to know that they have this feeling in common. It doesn't come up at the dinner table, and instead the brothers teeter in their consciousness of being together, and apart. Danny takes out his Palm Pilot and shows Elijah all of the things it can do, most of them work-related. There is something about this that strikes Elijah as familiar—Danny always loved having the latest toys. Elijah tries to share in the marvel. The main course arrives, and he tries to avoid the sight of Danny gnawing at the bones.

They do not stay for dessert. By the end of the night, all they can say is how tired they've become.

On the walk back to the hotel, Elijah realizes this is his first real adult trip. Even though he considers himself far from an adult, he can see that the trip marks some change. No parents. No teen tour counselors. No teachers chaperoning. This is what adults do. They book tickets and they travel.

If Elijah is reluctant to see himself as an adult, or even as a potential adult, seeing Danny as an adult comes easily enough. In Elijah's eyes, Danny has always been a grown-up. Less of a grown-up than their parents, but still much more of a grownup than Elijah's friends.

Danny was always so far ahead. None of Elijah's friends had a brother who was that much older. They would gather at the Silvers' house and become Danny's congregation, Elijah included. When they played basketball in the driveway, Danny always counted as four people, so the games were six on three, five on two, four on one. He always knew how to use the right curse words at the right time. If he wanted to change the channel, they would let him. Because he thought their shows were childish, and they didn't want to be childish. They wanted to know how to solve the secret puzzles the next few years would bring.

And then there was the armpit hair. Elijah spotted it one day when Danny was wrapped in a towel, finished with the shower. He raised his arm to deodorize—and there it was. Elijah told his friends, and the next time there was a pool party, Danny was the main attraction. He had no idea why the kids kept throwing the beach ball just over his head. Armpit hair was fascinating and scary and, more than anything, grown-up.

Danny's voice was beginning to sound like he was chewing ice cubes. His body grew taller and taller, like celery shooting.

He was thirteen then, Elijah almost seven. Now, ten years later, Elijah realizes he's older than Danny was. That all of those changes have happened to him, too. The changes that nobody has any say over. The biology—“growing” and “up” as a physical matter. The changes after—Elijah has to believe they're a matter of choice. Looking at Danny used to be like looking at the future. Now looking at Danny is like looking at a future he doesn't want.

His thoughts turn to Cal, to his friends, to home. He wishes that time was a matter of choice. That you could live your life controlling the metronome—speed it up sometimes, but mostly slow it down. Stay at the party for as long as you like. Prolong the conversation until everything is known.

To feel such a longing for his own life, even as he's living it—he wonders what that means.

Elijah falls asleep as soon as he returns to the hotel. In fact, he falls asleep a few turns from the hotel, but some mental and physical anomaly conspires to keep him upright until the door of the room closes. Danny is a little more fastidious before his own collapse. He hangs up all of his clothing and studiously brushes his teeth. Then he stands for a minute in front of one of the windows. He opens it wide, so the sounds of the canal and the laughter from the bar downstairs can segue into sleep.

Danny dreams of soldiers, and Elijah dreams of wings. They wake numerous times during the night, but never at the same time. Elijah thinks he hears Danny get up to shut the window, but when he wakes up, the window is still open.

Morning.

Breakfast.

“You fool,” Elijah says, glancing at the menu.

“What?” Danny grunts.

“I said, ‘You fool. ’ ”

Danny looks at the menu and understands.

“No,” he says, “I won't quiche you.”

“Quiche me, you fool! Please! ”

“If you say that any louder, you're toast.”

“Quiche me and marry me in a church, since we can taloupe!” Elijah is giddy with the old routine.

“Orange juice kidding?” Danny gasps.

“I will milk this for all it's worth.”

“You can't be cereal.”

“I can sense you're waffling….” Danny looks up triumphantly. “There aren't any waffles on the menu! You lose!”

Elijah is surprised by how abruptly disappointed he is. That's not the point, he thinks. He turns away. Danny pauses for a second, watching him, not knowing what he's done. Then he shrugs, picks up an International Herald Tribune, and begins to read.

Danny and Elijah are both museum junkies, each in his own way. It is hard to entirely escape all vestiges of a shared parentage. From an early age, both of the Silver brothers found themselves folded into the backseat of the family car for Sunday-morning excursions to the museums of

New York. There was never any traffic—driving through the city was almost like driving through a painting, the streets wider and cleaner than any New York street is supposed to be. An uncrowded city is a form of magic…and the magic only intensified as the museums neared. Sometimes the Silvers would walk amidst dinosaur bones and hanging whales. But most of the time, they made pilgrimages to color and light, brushstrokes and angles. Elijah saved the buttonhole entry tags from each museum as if they were coins from a higher society—the nearly Egyptian M for the Met, the hip capitalization of MoMA, each visit in a different color from the time before.

Danny fell in love with Starry Night long before he knew he was supposed to. Elijah would bring his Star Wars figures to the MoMA sculpture garden and have Princess Leia and Han Solo make a home in the smooth pocket of a Henry Moore. As they grew older (but not too much older), the brothers would hatch Saturday-night schemes to make the museums their home. As their babysitter looked on with amusement, Danny and Elijah would pore over From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler as if it were both guidebook and bible—a map and a divination. Sometimes the museums' floor plans would also be consulted, the bathrooms carefully marked and noted. As the ten o'clock TV shows said their eleven o'clock goodbyes, Danny and Elijah would whisper their plans, each more elaborate than its predecessor. We'll hide in the second-floor men's room, and when the janitor comes, we'll stand on the toilets so he can't see our legs. We'll hide under the bench in the room with the splatter painting. We'll spend the night in King Tut's tomb.

The Sunday-morning trips began to ebb as Little League, summer camp, and adolescent resentment appeared. Danny became a teenager, which Elijah couldn't begin to understand. (Danny told him so. Repeatedly.) All plans were off, because Danny had new plans of his own. The Silvers still went to the museum together, but with the near-formality of a special occasion. These were Big Exhibition trips—mornings of Monet and afternoons of Acoustiguided El Greco.

Later on, Danny and Elijah made their own excursions into the city, sometimes with friends but most of the time alone. Danny loved MoMA, with its establishment airs and Big Artist dynamics. Elijah was more partial to the Whitney, with its Hopper despair and youth-in-revolt aspirations.

Strangely, neither Danny nor Elijah felt a strong affinity for the Met. Perhaps the Temple of Dendur fails to amaze after the twentieth visit. Perhaps the museum itself is too palatial, too expansive to ever really know.

It should be taken as a measure of Danny's true New York soul that his first reaction upon entering the Academy is a vow to spend more time at the Met, in the Renaissance rooms.

Elijah's response is a much more succinct (yet also more entire) “Wow.”

There is a danger in living on a steady diet of Rothko and Pollack, Monet and Manet and Magritte. Danny and Elijah have an inkling of this now, almost immediately. They are struck, more than anything, by the details in the Academy's artwork. The faces in a painter's stonework. The downturn of a Madonna's eyes. The arrow's angle as it tears into Sebastian's side.

They do not know the stories behind all the paintings— such things weren't taught in Hebrew school. Perhaps that adds to the mystery and helps them approach in a strange state of wonder. Elijah is drawn to the paintings of Orsola—is she a martyr or a dreamer, a saint or a princess? He has no way of knowing. He asks Danny, and Danny mumbles something about enigmas. There is a happy complicity in their ignorance.

After an hour and a half, the Madonnas begin to look too much alike, and the Jesus babies are growing more grotesque in their bald adultness. Danny and Elijah are both losing sight of the details—it is harder to focus, and Danny is becoming restless. He wants to get to the synagogue in time for the noon tour. There will be more time for Art later.

They both agree on this.

A city presents many different faces, and it is up to the traveler to assemble the proper composite. Venice seems, at first, to be a simple enough city to render. It is the canals, the basilica, the shutters on the homes. It is the gondolier's call and the beat of the pigeon's wing and the church bell that chimes to mark the passing of an hour. To many people, this is all, and this is enough. A tourist does not want to be weighed down by realities, unless the realities are presented as monumental stories.

It takes a traveler, not a tourist, to search for something deeper. Travelers want to find the wavelength on which they and the city connect.

Danny is drawn to the ghetto. None of his immediate ancestors ever set foot in Venice (or Italy, for that matter). None of his friends have ever spent time there. He has never read or dreamed about life in such a place. And yet this is the destination he has chosen within a city of destinations.

(Elijah comes too and is moved and affected, but not in the same way. This is not what he has visited for. For him, the city is much more elusive, and will not know where he wants to be until he actually gets there.)

According to the museum in the ghetto, eight thousand Italian Jews were sent to concentration camps during the Holocaust.

Only eight of them returned to Venice.

This is the fact to which Danny attaches himself. If the ghetto itself is the bell, this fact is the toll.

The word “ghetto” comes from the Venetian jeto, which means “foundry.” The island upon which the Jews originally settled was formerly a foundry area (Danny learns). But the Jews, newly arrived from Germany and Eastern European countries, couldn't pronounce the soft j and instead called it geto. In the sixteenth century, the Jews were locked in from midnight to dawn; they became usurers because most other businesses were prohibited. (Hence Shylock, Danny thinks. The Merchant of Venice was the closest he came to finding meaning in Shakespeare in college.)

At one point in the ghetto, Jews had to wear yellow hats or scarves whenever they went out. Danny notes the color yellow—how can he not? The past reverberates so clearly, later on. Yellow hats, yellow stars.

As Elijah waits in the courtyard, Danny stands in the shade of a Sephardic synagogue—still in use, saved from the World War II bombings by an ironic alliance made between the Germans and the Italians. People begin to gather for the tour— a small, quiet group, almost all of them American.

The inside of the synagogue is dominated by black woodwork and red curtains. There is a separate section for women— a shielded balcony, high beyond the pulpit. The guide jokes that this means women are closer to God. Only the men laugh.

The guide goes on to say that there are now 600 Jews in all of Venice. Danny feels his somberness confirmed—how else can one feel when surrounded by such a majority of ghosts? You can find sorrow in the arithmetic, and you can find a bittersweet hope.

After the synagogue, Danny sees things differently. It's not that he's religious—at best, he would like to believe in God, if only he could believe it. Instead, his identity asserts itself. He sits in the plaza outside the temple and thinks about the 600 and what a crazy life they must lead. He wonders what it must be like to live in a place where Christ is in every doorway—well, maybe not every doorway, but he's sure it must seem that way. In American terms, it must be like living in the Bible Belt— with Christmas all year round.

Danny has these thoughts, but he doesn't share them. He can see that Elijah isn't in a similar space. Instead, he is sitting (shoelaces untied) in the sunniest corner of the plaza, watching a little redheaded girl in pink plastic sunglasses as she charges an unsuspecting flock of pigeons. There is a flash-flutter of wings—Elijah hunches over as the birds throw themselves skyward and fly thoughtlessly over the bench where he sits.

There is a small Judaica store open off the square. Danny walks to the window, but he doesn't go inside. Instead, he looks at the stained-glass kiddush cups and the tiny scrolls of the translucent mezuzot. Women from the synagogue tour step inside the store and touch the cases reverently. Danny turns away. He wants to go inside, but he doesn't want to go inside. It's his place, but it's not his place. Elijah is walking over now, and Danny allows this to be a

cue to leave.

They walk for some time without speaking. But this is a different non-speaking than it was before. Danny is still deep in his thoughts, and Elijah is letting him stay there.

Finally, Danny speaks, and what he says is, “It's incredible, really.” Then he stops and points back to the synagogue and says he can't imagine. He just can't imagine. Elijah listens as Danny wonders how such things can happen, what lesson could possibly be learned.

“I don't know,” Elijah says. He thinks of their parents, and how they'd be glad that their sons were here, thinking about it.

“All this history …,” Danny says, then trails off. Lost in it. Feeling it connect. Realizing the weight of the world comes largely from its past.

Although it is such a singular word, there are many variations of alone. There is the alone of an empty beach at twilight. There is the alone of an empty hotel room. There is the alone of being caught in a throng of people. There is the alone of missing a particular person. And there is the alone of being with a particular person and realizing you are still alone.

Elijah parts with Danny in St. Mark's Square and is at first disoriented. The courtyard is filled with thousands of people, speaking what seem to be thousands of languages. People are moving in such an everywhere direction that there is simply nowhere to go without firm resolution. Elijah's first instinct is to steal a quiet corner, to purchase a postcard from a hundred-lire stall and write to Cal about all the people and the birds and the way tourists stop to check their watches every time the bell tolls. He would sign the postcard Wish you were here, and he would mean it—because that would be his big threepenny wishingwell birthday-candle wish, if one were granted by a passerby. Cal would make him smile, and Cal would make him laugh, and Cal would take his hand so they could waltz where there was no space to waltz and run where there was no room to run. He thinks about her all the time.

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

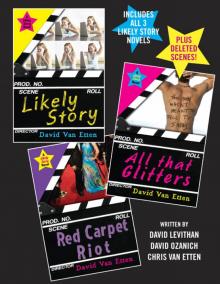

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!