- Home

- David Levithan

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) Page 4

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) Read online

Page 4

I could hear her from the bedroom and I was sure Aidan could hear her from the den.

There were also Dad’s calls, checking in. “They’re doing homework,” she told him. “It’s like nothing happened.”

But that didn’t make any sense. The fact that Aidan was quietly doing homework was total evidence that something was off. Ordinarily on a day home from school he’d be texting his friends nonstop—they had this game they’d play where three of them would email a word at the same time, and then they’d Google the three words together—badger Halloween cloud, for example—and see what the funniest result was, usually a really weird video. Or he’d find a multiplayer game where he could dial in and stave off zombies with other players from time zones where school wasn’t in session, whether it was Tokyo or Berlin. At the very least, he couldn’t sit for more than an hour without getting up for a snack, usually stopping by wherever I was to mess with me.

But Aidan didn’t want to talk to me now, or to anyone else. He didn’t even snack.

Couldn’t Mom see that?

* * *

—

I kept waiting for Aidan to sneak up to the attic. I left my door open in hope of catching him.

When he didn’t go up there, I went myself. Walked to the dresser. Felt for a wind. Opened the doors and found nothing but air and wood. Closed the doors. Opened them again. Pretended to walk away, then quickly turned back and opened them a third time.

Nothing. Just a dresser.

When I got back to our room, Aidan was there, getting some books from his backpack.

“Find anything?” he asked casually.

“Nope,” I told him.

He went back downstairs.

* * *

—

The only person who asked to talk to me and Aidan on the phone was Aunt Brandi. Mom passed it over to me first, then left me alone when I made it clear I wasn’t going to talk until she stopped hovering.

“How’s it going over there?” Aunt Brandi asked.

“Great,” I said. It was kind of an automatic response.

“Is that so?” Aunt Brandi’s low voice didn’t seem to believe me. “I know you’re excited to have Aidan back, but I can’t imagine it’s an easy time.”

“It’s okay.”

“Mom told me where Aidan says he was. That must be a lot to take in.”

“It doesn’t really matter what he says, as long as he’s back.”

“Of course. But it’s okay to think it’s a little strange. You know that, right?”

“Sure.”

“And are your parents behaving themselves?”

This was something that Aunt Brandi always asked me when she called.

“Well, Mom’s mad and Dad’s at work.”

“That’s my assessment too. Listen, Lucas—will you do me a favor? Can you take care of your brother and try to help him out however you can? I’ll come down over the weekend to help out too, because no matter what Aidan says, he’s going to need us in his corner now. Especially with you going back to school tomorrow.”

“There’s no way of getting out of it, I guess.”

“Nope—school’s the plan. But, believe me, that’s much better than sitting around on pause for any longer. Anyway, can I talk to Aidan? Is he there with you?”

“I’ll go get him.”

“Thanks, Lucas. You know where to reach me, anytime.”

I walked down to the den and passed the phone over to Aidan. Just like I hadn’t really started talking until Mom left, he didn’t really talk until I left.

I wondered if Aunt Brandi would be able to get the truth out of him. She was Mom’s youngest sister by a stretch, halfway in age between Mom and us. She lived in the city and worked as a graphic designer for a T-shirt company. This meant Aidan and I were always getting free T-shirts with random slogans—my favorite was a penguin standing in the middle of a crowded street asking, “Where can I get some ice?” while Aidan loved one that showed a snail trying to swipe a phone twice its size.

“Did you have a good talk?” Mom called out from the study before I could get back to my room.

I poked my head in. “Yeah. She said we’re going back to school tomorrow.”

Mom nodded. “I don’t see why not.”

“Even though it’s Friday?”

“Last time I checked, there was still school on Fridays. And you and Aidan have missed enough already. Your teachers can catch you up tomorrow so you won’t be so behind next week.”

She started asking me about homework, and I was going through it class by class when Aidan barged in, the phone still in his hand.

He glared at our mom. “I can’t believe you told her! Why did you tell her?”

“Because she’s my sister and I tell her everything.”

“But that’s mine! Aveinieu is mine. You even told her its name!”

“Why does that matter? She’s not going to tell anyone. And, quite honestly, I needed her opinion, because I don’t quite know what to do with your story, Aidan. Until you tell us what really happened, I’m at something of a loss. Officer Pinkus told us to be patient with you, and we will be. I know that whatever happened, it had to have been a lot. And the last thing I want is for you to disappear again. If you don’t want to let us in, that’s fine. But this is something your dad and I and Lucas are going through too. And we need to do what we have to in order to navigate it. For me, that means talking to Brandi. I’m not going to be telling your story to the mailman or your teachers or even your grandparents. The last thing I want is for anyone else to hear it.”

Mom had just thrown a lot at him, but there was only one thing Aidan caught.

“So you don’t believe me?” he said.

Mom took a deep breath. “It’s just very hard to believe, Aidan. But if it’s the story you want to tell, I’ll support that. I’m only worried—we’re all worried—that there’s something underneath that you’re trying to hide. And it will be much better for you to let it come to the surface, so we can deal with it together.”

Before, if Mom called Aidan on something, he would match her attack with one of his own. If she tried to pin him down with a sentence, he’d use a sentence to get out of it. If she tried to pile on a paragraph, he’d build his own paragraph and push it over to her. So I was expecting him to really let go of some words now, to say something like, If you really want some things to come to the surface, let me show you the thoughts that are coming up right now.

But instead, “It’s the truth” was all he said. Then he handed the phone to me and went back to the den.

I passed the phone to my mother, who also looked like she’d been expecting more back from Aidan. That was how they connected.

Now she asked me, “I’m not off base, am I?” Then, realizing who she was talking to, she walked it back. “Never mind. We’ve all been under a lot of strain. Brandi said to keep that in mind, and to make allowances.”

“Are you sure that includes going back to school tomorrow?”

This got a half smile from Mom, which under the circumstances counted as a full smile.

“Yes. It does.”

* * *

—

We pretty much stayed in our separate rooms until three o’clock. Then Mom caught Aidan making a move for the front door. I could hear them from our bedroom.

“Where do you think you’re going?” Mom asked.

“To Glenn’s. School’s over. He texted that he’s home.”

“You aren’t going anywhere. He can come here another day. You’re grounded for the near future—you are not to leave this house without an adult around.”

“Not even to Glenn’s?”

“Not even to Glenn’s.”

“That’s not fair!”

“I’m not sure you get to be

the judge of fair and not fair right now, Aidan.”

“Fine!”

Aidan’s footsteps stomped toward me, and soon he was back in the room. I pretended to be doing my homework.

He wasn’t fooled.

“I assume you heard all that?” he said.

“Mmm-hmm.”

“I guess I’m a prisoner here.”

I didn’t point out that we’d all been prisoners for six days while he was gone. Instead I said, “It doesn’t make much sense anyway.”

“Yeah. What would happen if I went to Glenn’s house?”

“No, I mean, what’s the point of grounding you and keeping you here if the way you get out is up in the attic?”

“That’s not funny.”

“It wasn’t meant to be funny. It was meant to be, like, logical.”

“It’s not going to open up again.”

This intrigued me. “How do you know?”

Instead of elaborating, Aidan said, “I just know.”

Then he left the room.

* * *

—

It felt like Mom spent the afternoon on the phone. “He hasn’t told us anything yet,” she kept saying. “He hasn’t told us anything at all.”

* * *

—

At around five, Aidan went up to the attic. But he was back down in two minutes and gave me a dirty look for checking up on him.

* * *

—

Dad came home. We had dinner. I thought we were supposed to be acting like everything was normal, but it didn’t feel normal. Aidan wouldn’t talk or eat. Dad and Mom kept looking at him. They didn’t pay any attention to me. The mystery filled the room so much that it was hard to breathe.

Aidan was no longer missing, but now it was like the answers to his disappearance were missing instead.

17

Aidan and I didn’t say much the whole night. Then we were in our room and the lights were out and both of us were there in bed, trying to sleep and not sleeping. Sharing a room, this was often the space for us to let off what was on our minds, what might keep us awake or simply what we needed to tell someone else before we forgot it the next day. Usually it was Aidan who spoke up, whether because he had more to say or because he needed an audience more. Sometimes he’d just be telling me about something he and his friends had found online. (“Did you know that some people dress up their pet badgers for Halloween?”) Or maybe he’d be venting about some injustice, online or off. (“There are three guys in this house and only one Mom, so I don’t see why, statistically, it makes sense for us to have to put down the toilet seat every single time after we pee. Especially in our bathroom.”) Mostly my job was to laugh or to agree.

This time I knew he wouldn’t be the one to start things off. When a thought came into my mind, I almost left it there. But I was curious, and the curiosity spread to my tongue. There in the darkness, it was easier for curiosity to take over.

“Did they speak English?” I found myself asking Aidan, although I made it sound like I was asking the air.

“What?” he asked back, even though it was pretty obvious what I meant.

“In Aveinieu. Did they speak English? That’s what I’ve never understood about most books where people from our world go into a fantasy world. All of the creatures in the fantasy world speak English. That seems too convenient.”

Was I asking this to make fun of his story? Was I asking in order to catch him in a lie, to make him explain things until he contradicted himself and proved himself to be a liar? Or was I simply curious about how it all had worked for him, back in Aveinieu? There’s no clear motive, except for this: Sometimes we ask questions because we hope the answers will tell us why we asked the question in the first place.

He could’ve blown me off. He could’ve told me to shut up. Maybe because we were in the dark, maybe because we weren’t looking at each other, he did something else instead.

He told me more of the story, and made it sound like the truth.

“The Aveinieu didn’t speak English, or any other language someone from our world would know. But I wasn’t the only person from our world there. There was this older woman, Cordelia, who’d lived there since she was my age. So for fifty years or so. And she’d learned how to talk to them. She was the one who found me, and she became my translator. She tried to explain it all to me.”

“How long were you there?”

“I don’t know. Their days and nights aren’t like ours. But probably a month?”

“And did you live with Cordelia?”

“Yeah. She took a lot of us in. The ones from our world.”

“How many of you were there?”

“Seven or eight.”

“Which one—seven or eight?”

“What is this, a quiz? Forget I said anything, okay? Forget all of it.”

“Come on! Tell me more.”

“Why? So you can tell Mom and Dad?”

“I won’t tell anyone.”

“You better not. Especially at school tomorrow. Do you understand?”

I imagined the reaction I’d get if I tried to explain to my friends what Aidan said had happened.

“Do you really think I’d tell anyone?”

“All I’m saying is, you better not. Now stop asking me questions. I need to go to bed.”

I should have left it there. But I wasn’t sure I’d ever get him to talk again. So I said, “Can I ask one last question?”

“What?”

“Why did you come back?”

For a while I didn’t think he was going to answer. Then, right before I fell asleep, I heard him say, “It wasn’t my choice.”

18

Normally, Aidan and I took the bus to school. I’d assumed that was how we were going to get there on the first day back. But instead, Mom and Dad informed us over breakfast that they’d both be taking us to school—and coming in with us, to meet with the principal and the guidance counselor.

“That’s not embarrassing or anything,” Aidan mumbled.

“If you were worried about being embarrassed, you should’ve thought twice before you—” Dad started. But he couldn’t—wouldn’t—finish the sentence. It was like he didn’t want to mention the possibility of Aveinieu out loud.

None of us finished the sentence for him.

I guess we didn’t want to talk about it either.

* * *

—

“My teachers, the principal, the guidance counselor—you haven’t told any of them what happened, have you?” Aidan asked on the way over.

Both of our parents looked at him in the rearview.

“No,” Mom said. “And nobody’s supposed to ask. They’re supposed to leave you alone.”

Aidan looked relieved. But I thought: Who wants to be alone?

* * *

—

Principal Kahler was grinning like a military general who’d just won a battle. As if to balance him out, Mr. Lemon, our guidance counselor, looked like he was trapped on an icy lake and the temperature was starting to rise into the nineties.

“We had an assembly yesterday,” the principal told Aidan, “and in addition to celebrating your return, we also warned the student body that our no-tolerance policy extends to anyone who doesn’t respect your privacy in this difficult time. No one is to put you on the spot, make you feel uncomfortable, or treat you any differently than they would have treated you if you’d been in school this past week. And, frankly, that applies to the teachers as well as the students. If anything happens, you have permission to come straight to me or Mr. Lemon. In return we expect you to resume your studies and continue to be a valued member of our middle school community. Does that sound like a good deal to you?”

“Yes,” Aidan replied. Principal Kahler was, I thought, be

ing really nice, but Aidan still looked like he was getting detention.

“You and I will get to talk fifth period,” Mr. Lemon added. “I’ve already arranged it with Ms. Simon.”

I could see that Aidan wanted to groan out, “Oh, great.” But he held it in.

“That’s very generous of you,” Mom said. As if it wasn’t Mr. Lemon’s job.

The first bell rang. Principal Kahler stood up to shake our hands.

“Let’s see how this goes,” he said.

* * *

—

Glenn was waiting for Aidan outside the main office. Mom and Dad looked happy to see him. Aidan looked embarrassed.

“Heya,” Glenn said.

“What’s up?” Aidan said back.

“Not much.” Glenn smiled. “You?”

Aidan shrugged. “Not much.”

“Cool.”

“Cool.”

Then they walked off without giving the rest of us another look.

This left me with Mom and Dad.

“Promise you’ll call us if anything goes wrong,” Dad said.

“Uh, sure,” I promised. I was a little curious what Dad meant by “wrong”—Aidan running away from school? Bullies bullying his story out of him? Unicorns invading fifth period in order to get him back? But I also knew if I asked for clarification, I’d probably end up talking to them past the late bell, and I really wanted to get to homeroom and have my regular life begin again.

“Bye!” I said so loud and cheery it probably looked like I was auditioning for the school musical.

While I walked through the hallway, I could see a few people looking at me, but not too many. My best friends, Busby and Tate, found me while I was at my locker. Although they’d offered to have me over to their houses, I hadn’t really talked to them while Aidan was missing. Now I could see they were torn between playing it cool and asking me everything.

It was Busby who broke first, her voice barely a whisper.

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

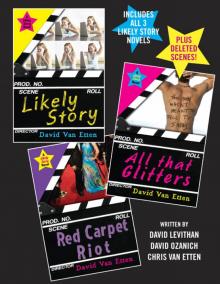

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!