- Home

- David Levithan

How They Met and Other Stories Page 8

How They Met and Other Stories Read online

Page 8

along the lines of Wow. I once asked Randy how he knew

that he had fallen in love with his girlfriend, Amy, and he just

looked at me like it was the hardest question in the world.

I expected some floral, florid explanation, about the air

lightening and flute music filling his ears. This relationship

that had him so transfixed—I expected a masterpiece of

sentiment, one that would make me so happy for him and

so empty inside. Instead he just turned to me and said,

“The minute I knew I was in love was the minute when

there was no question about it. One night I was lying

in the dark, looking at her looking at me, and it just

was there, undeniable.”

There is no question about it. I look in amazement

as Mandy pushes herself up the stairs, not looking up

at me, concentrating on her footwork. I want so much

for her to reach the top. I want her to reach me

at this very moment. I picture myself embracing her

when she makes it, looking into her eyes for the

confirmation of my feelings. What do I feel? If it isn’t

love, then it’s certainly the potential for love, the realization

that there’s more to us than liking and dating and being

each other’s Pictionary partners. I’m so happy. I’m so

afraid. Does she feel the same way? All I know

is that I know. When she reaches the top, maybe I’ll

dance with her to the piped-in non-music drifting

from the ceiling. I’ll do anything—I want to do something

totally strange and new and special. I want to hold her.

I want to sleep with her—fall asleep with her in my arms.

I want to wake up that way. I’ve never seen her asleep.

All of these strange impulses—I want to tuck her in.

I want to be there, and be there, and be there.

And then she falls.

It’s over before I can register what’s happening. Her foot

hits one of the steps and, well, she trips. It isn’t dramatic—

she doesn’t fall down the escalator or anything.

It isn’t even good comedy. She just stumbles face-first onto the

steps. Then she pushes herself up and rides the rest of the way

down. I run to her—it’s as if I’m moving doubly, being

carried as I go down. I get to her. I can’t tell if she’s crying

or laughing. “I can’t do anything!” she says, brushing back

her hair, and I see her exasperation isn’t serious. I say

something along the lines of “Don’t be silly, it could’ve

happened to anyone,” and gather the things that fell

from her bag. She’s still sitting when I’m done, so I offer her

my hand. She doesn’t get up—she just keeps looking at me,

not at my hand but at my face. I put the bag down and sit

beside her, right there on the floor of the mall. “Are you

okay?” I ask. She says, “I fell,” and I say, “I think I’ve fallen, too.”

It’s never like the movies, is it? A great romantic moment, and

clunky, corny things just tumble out. “Oh,” she says, and I wonder

if she’s saying it just to see what I’ll offer next.

“Yeah,” I reply, saying it to see what she’ll say next.

Which is, “You have to be careful.” Now what does that mean?

Indirect discretion. No one wants to fully commit—

everyone’s afraid that they’re misinterpreting because no one

is talking straight. Playing the old What Are You Thinking? game.

You have to be careful. Mandy has skinned her hands

and her lip has a little cut in one of its corners.

“Sometimes…” I say.

“Well…” she answers.

And I can’t take it anymore. She just looks at me, no help at all.

But, then again, all I’m doing is looking at her. A silent standstill.

A time for something. On her lip, there’s a little drop of blood.

I kiss her anyway. At this particular moment,

there’s just no question about it.

THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE WHO MEET ON AIRPLANES

This was ten years ago. I was a junior in boarding school, heading back to campus the Monday after Thanksgiving. After three rounds of leftovers, I was ready to return to the dorm, to our well-honed methodology of procrastination, to that last gasp of late-night madness before exams settled in and Christmas came.

I had planned my flight down to the last minute: I’d finish the book I was reading, proof a paper I had due, and sneak in a forty-five-minute nap before touching down in Boston. I had my headphones to protect me from screeching children and talkative adults. I had five sharpened pencils in the front pocket of my bag. I was ready to go.

I usually liked to sit in row seventeen, because seventeen was my lucky number. This time, however, I was seated in row fourteen. I decided not to take this as a bad omen. I was not a person who normally believed in omens. Only luck.

I am always early to airports, and thus I always board when my row is first called. The overhead compartment gaped for my hand luggage. I fed all the seat pocket detritus into its maw—the shallow magazines, the safety instructions, the plastic-wrapped blanket, and the paper-clad pillow. I would keep only what was essential: my headphones, A Room with a View, my research paper, and three of the sharpened pencils.

As the plane filled up, I began to get hopeful; the seat next to mine was still empty, leaving me with plenty of legroom. I took up my book and started to read. I lost track of where I was, and was brought back by a tap on my shoulder. She might have said excuse me—I didn’t hear. I looked up into the aisle. And there she was.

She was my type of pretty. Short black messabout hair, falling wherever it wanted. She was wearing a red sweater that somehow brought out that green of her eyes. She had a nice smile. I recognized this in the second before I tried to stand, even though my seat belt was already on. I continued to notice this as I unbuckled the seat belt, as she slid past me. Once she sat down and started going through the bag on her lap, I said hello.

I had never talked to a stranger on a plane before, nothing above the cursory regards. This was because I am in general an antisocial person, and because I’d never been seated next to anyone even remotely desirable. Instead I had an unerring ability to be partnered with the overweight business traveler who brought no reading material, or the father whose poor wife was across the aisle, forced to manage the demands of their children. Never anyone my own age, traveling alone. Never anyone who was my type of pretty.

She said hello back to me and scavenged deeper into her bag. I could feel my courage wavering. I tried to think of something profoundly interesting and not at all stalkeresque to say, but nothing came. I am a very strong believer in personal space, and I didn’t want it to seem like I was storming hers. I was about to retreat to my headphones when she finally found what she was looking for—a copy of A Room with a View. The same edition as my own.

I’d always had (and still do) two rules for myself: If I were ever to pass a busker on the street who was playing the same song that was on my headphones, I would give away all the money in my wallet. And if I were ever to be riding the T and spy someone reading the same book as me, I would strike up a conversation. Again, not seeing it as an omen, but as luck.

I figured the rules of the T applied to air travel as well. Of course, I’d never actually planned what I was going to say to the person who was reading the same book as me—my thoughts had never gotten that far. So I was entirely unprepared when I looked over to her and said, “It looks like we’re reading the same book.”

I took mine off my lap. She looked at it, then looked at hers

. She could have easily dismissed it as a little coincidence, a minor disturbance. But instead she looked back up at me and said, “Wow. Neat.” Not at all sarcastic. No—she got the subtle wonder of the situation.

I knew right then that we were going to get along.

Her name was Rory. I introduced myself as Roger. She had been visiting her father for Thanksgiving, and was now going back to her mother’s house in Newton, where she went to high school. We were both aiming to be English majors when we went to college, and neither one of us was reading Forster for school.

I think one of the highest compliments you can give a person is that when you are talking to her, you are not thinking about the fact that you are talking to her. That is, your thoughts and words all exist on a single, engaged level. You are being yourself because you aren’t bothering to think about who you should be. It is like when you talk in a dream.

She spied my AP English research paper in the seat pocket. I ended up proofing her Virginia Woolf while she marked up my Wilfred Owen with one of her own (yes) sharpened pencils. We talked about our Thanksgivings, which really meant talking about our families in all their fragments and fissions. We began to see signs everywhere—in the fact that we’d both ordered the vegetarian meal even though neither of us was strictly vegetarian, in the fact that we were both wearing contact lenses, in the fact that we both had cousins named Jessie who were our favorites.

We talked through the in-flight movie. We talked in such a way that the flight attendants assumed we knew each other. We talked so much that we started to feel like we did know each other, as if every shared story could create an actual shared past.

Then the turbulence hit. I am an easy flier; I cannot tell you why, no more than I can tell you why I am afraid to climb down ladders. (Not up, just down.) From the moment the seat-belt light came back on, it was clear that Rory was not an easy flier. She clutched at her armrest, changed her breathing. She apologized to me and made fun of her paranoia. But I could tell that it was fear—a pure and genuine fear, the kind that rebukes rationality no matter how pleasantly or clinically the rationality is offered.

“My doctor gave me drugs, but I think I’m even more afraid of them,” she told me. “He said to throw a blanket over my head and pretend I wasn’t really on a plane. That was very helpful.”

I took out her copy of my book. She was about twenty pages ahead of me, but that didn’t matter. I freed her blanket from its plastic protection and threw it over both of our heads. Then, by the trail of light along my arm, I read to her. We walked around Florence as the characters courted disapproval. After a particularly sudden dip, Rory grabbed my hand without asking, and I let her without mentioning it. I kept reading, turning the pages with my one free hand as all our air turned to breath and the light of the world came in through a scrim of blue cotton. When the plane steadied off, I put the book down for a moment. Rory leaned into my shoulder with her eyes closed and a half smile on her lips. Gently, she found the right angle, the comfortable inclination. I let the book drop. I let us sleep. Two strangers under a blanket, in between two versions of home.

That is how we met. Within a few hours, we were sharing a cab even though we didn’t live in the same part of town. Within a week, we were planning to meet up in Boston every chance we got. Within two months, I was sure I was in love. We dated all of senior year and decided to stay together. We went to colleges in the same city, and when we graduated, she got a job teaching in San Francisco, and I followed her there. I got a job at a family-oriented Web site just when such things were big, and left to become a teacher myself right before the Web business hit its first snag. We were married nine years to the day we met. We have become—although I’d never say this out loud—something like a model couple. The secret? We like each other. I mean, we really like each other. We know when to keep our space and when to share it. We are surrounded by friends—some of them dear, some of them who come with the territory.

We always loved to say If I’d had a Monday-morning class, I never would have met you. Or If you’d been reading something else, none of this would have happened. We didn’t believe in fate, but we believed in serendipity. We felt very lucky.

We threw a party to mark the tenth anniversary of the day we met. We had it the Sunday after Thanksgiving, for all our friends who were returning from home, ready for a different kind of meal. Our friend Tyson brought his new boyfriend, Geoff, a flight attendant who we’d never met before. Our friend Gwen brought her boyfriend, Ted, an architect we were trying hard to like. And our friends Marcy and Will came alone, even though secretly we wished they had come together.

Both Rory and I like telling the airplane story—in no small part because it is our story, but also because we like to think it’s a good story as well. Somewhere toward dessert, Ted asked us how we met. Tyson, Gwen, Marcy, and Will had heard it before, but they egged us on nonetheless. (I had been roommates with Will at the time, and he always liked to add the postscript—the look on my face as I came through the door that Monday night; even before I said a word, he knew something life-changing had occurred.) So Rory and I tag-teamed the telling—from me hoping for legroom and her hoping to catch the flight, to the discovery of the book in common, to the similar meals, oncoming turbulence, and blanket-covered reading. Of the audience, Geoff seemed to like the story the most. Perhaps because he spent his days in airplanes, perhaps because he and Tyson were newly in love.

Afterward, he and I were in the kitchen, putting the dishes into the dishwasher. It had been nice of him to volunteer—more than most of Tyson’s previous boyfriends had done. I was sure Rory was pointing this out to Tyson, somewhere in the other room.

“That’s so funny, what you said about your lucky row,” Geoff said to me. “I know this is going to sound strange, but didn’t you say you’d requested row seventeen?”

I nodded. “I did. But when I checked in, it was switched. They probably made a mistake. A very lucky mistake, as far as I’m concerned.”

“And what airline was it?”

I told him the airline.

“And what airport did you leave from?”

I told him the airport.

“Hmmm…”

He’d stopped drying now and was just looking at me, doing some mental math.

“What?” I asked.

“Oh, this is crazy. It was ten years ago, you said?”

“Almost to the day.”

“Okay—now I’m going to ask you a really strange question. Do you by any chance remember what the man behind the ticket counter looked like when you checked in?”

“No. I’m not even sure it was a man. Why?”

Geoff’s eyes gleamed. He took the towel out of my hand and tilted his head to one of our kitchen chairs. “You’d better sit down a sec,” he said, “and let me tell you about Al Schwartz.”

Al Schwartz was a legend in airline circles. He wasn’t a pilot or a flight attendant. He wasn’t in management or a leader of one of the unions. No, for almost forty years he worked the ticket counter, without once missing a day of work. He was the Cal Ripken of airline employees. But even more than that—he was a famed matchmaker.

He didn’t do it often, but when he did, legend said that he almost always got it right. It worked like this: An unmarried person would arrive to check in for his flight. If he was already booked between two people and Schwartz had an instinct about him, he would be switched to a new row with an available seat next to his. Then a second unmarried person would check in. If Schwartz felt strongly that this person would get along with the first person, he would seat her in that available seat. The rest would be up to them.

At first, he did this in secret, not telling a soul. (It was rightly believed that supervisors wouldn’t take too kindly to this meddling; it was something short of a flight attendant flirting with a passenger, but it still smacked of impropriety.) After many years, however, word got out. Pilots and flight attendants leaving from Schwartz’s airport would wonder if th

eir flights had been graced with prospective lovebirds. Bets would be made; results would be tallied. Schwartz denied everything and kept doing all he could. When his colleagues would ask him to set them up, he’d always shake his head. He only made matches when the people involved had no idea.

“But where is he now? How can I find out if he had anything to do with Rory and me?” I asked Geoff.

“He retired a while ago,” he told me. “But don’t you worry—I’m sure I can track him down. Consider it my anniversary present.”

Two weeks later I got a postcard from Paris. On the back, Geoff had scribbled an address in Nevada, adding No phone with two underlines and Good luck! with three.

I didn’t tell Rory. I know I should have, but part of me liked having this secret, wanted to be able to present her with the full story. So I kept the postcard hidden in my desk and pondered the letter I knew I had to write.

I was out of practice. I hadn’t written a true letter in an embarrassing number of years. I communicated with my friends through e-mail, and didn’t really communicate with anyone else besides my friends. I knew writing Schwartz wasn’t something I could just toss off. I knew it was something I had to do by hand.

I waited until the quietest moment possible to write. I will not recount my drafts (or even count them), but will simply say that this is what I ended up with:

Dear Mr. Schwartz,

My wife and I met on [here I gave our airline and flight number] from [the airport] on [the date]. A friend just brought it to my attention that you might have had something to do with this. I was supposed to be in the seventeenth row, but was switched at check-in to seat 14B. If you had nothing to do with this, I apologize for taking up your time. If you did in fact seat my wife (her name is Rory Wright) and me together on that day, I would appreciate it if you could respond to the address below. Either way, I thank you.

Sincerely,

Roger Lewis

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

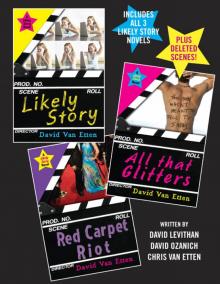

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!