- Home

- David Levithan

The Full Spectrum Page 2

The Full Spectrum Read online

Page 2

“What?” I could only hear the sound of my heart crashing against my breastbone, a deafening noise inside of me.

She laughed a little, drumming her fingernails on her thigh. “I dare you,” she repeated. “I dare you to kiss me.”

I couldn't feel my body. The room seemed ridiculously hot, and the pungent smell of the incense was making me dizzy. In between tracks I could hear the CD skipping in the stereo. I was frozen, my hands dead weights on the bedspread, and Rose just sat there and looked at me. Finally I lunged forward, put my lips on hers, and felt the heat of her breath on my face. We kissed slowly, timidly, my eyes squeezed shut. It hurt how much I wanted it, how much I wanted Rose. I found myself slipping my tongue out of my mouth, pushing it into the warmth of hers. I thought I would explode. Rose pulled back slightly, gave a small smile before shifting away from me, standing up and going to the CD player, changing the album. I sat on the bed, not sure whether to cry or to thank her. She turned on the lights, a cue that the moment was over. I suggested we watch more TV and she shrugged. Downstairs we channel-surfed through the infomercials and B-movies of late-night television. She was detached and cold. I wanted to scream. I sat on the couch in the living room next to her, sometimes munching leftover popcorn from the bowl we had made earlier. The cold kernels tasted stupid on my tongue. We finally gave up on the TV and decided to go to bed. Upstairs, Rose rolled her sleeping bag out on the floor, but instead of changing in my bedroom like we always did, she took her pajamas out of her schoolbag and went into the bathroom. I stood awkwardly next to my bed, wondering what I had done wrong.

The next Monday Rose didn't come to school. I ran home from the bus and dialed her number before I had even put down my backpack. Her mother answered.

“Hi, is Rose there?”

“Is this Courtney?” her mother asked in a sharp voice.

“Yeah,” I said.

Her mother coughed a little. “Rose can't come to the phone. She's indisposed.”

Indisposed. She pronounced the word long and hard. I had to go to the big dictionary on the shelf in the living room and look it up. Indisposed. To be averse, disinclined. To be or feel ill, sickened. To be rendered unfit, disqualified. I blinked, shut the book, and slid it back into place, next to the encyclopedias and the anthologies of Shakespeare. I hoped Rose was okay.

When Rose stopped talking to me, I just kind of accepted it. I didn't know what else to do. Our other friends were curious. Did something happen? Did we have a fight? I would shake my head madly or shrug my shoulders, trying to look aloof. They would shrug back, talk about how strange she was. Maybe she was having her period. I swallowed all the confusion and regret deep inside me, and nodded at their conclusions. Strange.

I thought I would be able to finish out the school year avoiding Rose as it seemed she wanted me to, but there was the marching band trip to Ocean City, Maryland, for a parade. We had been preparing for it all year. It was an overnight trip, and we would be staying in a hotel. I had signed up to share a room with Rose and our two friends Patricia and Julie. I panicked. One day after practice I went to the parent in charge of arranging the trip. “Is it too late to change room assignments?” I asked, making a pleading, desperate face. The woman had a perm and was wearing a sweatshirt with our high school's emblem on the front.

“No can do!” she said cheerily. “All the rooms are packed. If I switched you I'd have to switch other girls' rooms around, too. It's only two nights, dear. I'm sure you can work things out.”

The day before the trip I acted sick, told my mother I was vomiting and couldn't go. She took my temperature and patted my head when it read the normal 98 degrees. “Just nerves,” she told me with a smile. “It's such an exciting trip, you'll have so much fun.” That night I cried so hard into my pillow that my brother banged on the wall from his room, yelling for me to shut up.

On the trip I just stayed quiet. I figured if I didn't say anything it would look okay, normal. I listened to my headphones constantly and stayed in the room watching television while other kids played Ping-Pong and went in the swimming pool. Rose stayed out of the room, hanging out with some of the boys from the drum section. They smoked cigarettes outside by the Dumpster and she would come back reeking of Newports. Julie thought Rose had a crush on the guy who played snare. I sat stone-faced on the bed and said nothing. It rained the day of the parade and our flags drooped sadly; they made us march because it was only drizzling when we started. “Just a little spritz,” our coach encouraged us merrily. Our costumes were so cheap that the orange sashes bled onto our leotards, looked like rashes up and down our legs and arms. It was our last night in the hotel. We had some free time before we were scheduled to go out to dinner at some seafood restaurant on the boardwalk. I went into the room to get my headphones, thinking everyone was downstairs. When I came in, the bathroom door was slightly ajar. I saw Rose coming out of the shower, naked. “What are you doing?” she screamed. Her eyes became daggers and she slammed the door hard. I started to shake and walked out of the room, started walking down the hall, half running. At the end of the hall I collapsed into a heap in the corner by some fake plant and sobbed, burying my head between my knees. I heard the ding of the elevator opening. Soon Patricia and Julie were by me.

“I kissed her!” I yelled. “I kissed Rose! That's why she hates me! I kissed her!”

I was gulping for air. Patricia and Julie were staring at me. I thought about how I was losing more and more friends, about how stupid that kiss had been, how it had ruined everything. Patricia leaned forward and hugged me. “It's okay,” she said quietly. “It's really okay.”

The next week at school Patricia must have said something to Rose. She came over to me one morning before homeroom and asked me to talk. I picked up my book bag and walked down the hall with her. She looked at the ground when she spoke. “I'm just not like that, okay?” she said in an angry rush of words. She glanced at my face and then looked back at the ground again. “I just don't want people to think I'm like that. You can be whatever you want, but I'm not … I'm just not.”

I was fiddling with the strap of my book bag, the one that was frayed and dangling. I shrugged. “Okay,” I said, my voice hollow. I wanted to go back to my friends, I wanted Rose to be something that never happened. She mumbled something about being late and walked down the stairs, lost in the crowd of teenagers going to first period. I walked back to my locker and tried not to think about it. I consoled myself with the idea of college, that I could move far away to some city and have a girlfriend and be queer and make out with her whenever and wherever I wanted. I tried not to think of Rose anymore. I told myself that a kiss was all I had wanted.

A Gay Grammar

by Gabe Bloomfield

This is not a story in which a helpless teenager is beaten. This is not a story about sexual repression. This is not a story about rape.

It doesn't involve confusion, it doesn't have any major breakdowns.

Nobody attempts to commit suicide in this story.

This may be an uncommon story. The main character is happy. The main character rarely feels pressured, except when it's by schoolwork. The main character is gay. But he is not gay-bashed; in fact, his sexual orientation barely feels part of him anymore, because he and his family and friends have so easily accepted it into their lives.

The main character does not feel gay. He just feels like himself.

The main character is I.

If you think that the last sentence of the previous section looks odd, or even wrong, you're probably not alone. The vast majority of English speakers would actually have said “The main character is me” (or, to avoid the conundrum altogether, “I am the main character”). This is grammatically incorrect; however, this type of grammatically taboo construction has been used so often that it has been practically accepted into English grammar as what is right.

You see, the verb to be does not take an object; it takes a predicate nominative, which is why you have to use

I (the nominative) instead of me (the accusative). But that hardly matters. What matters is that if I said that sentence while talking to a crowd of people, I would get a lot of odd looks. Many people think that it's wrong, although most would not voice their opinion. My friends and parents would look at me and turn to one another and sigh, because they know that I'm a nut for grammar and that I say it the right way rather than the way that sounds right to most of the people in the room.

This is oddly like being gay. My friends and parents know it too well to notice, or if they do, they just smile. Just another one of my quirks, part of who I am. Other people notice it, too. It's not that hard to tell. Somebody could even say that it sticks out. But they may be confused, unsure, even frightened. Some people know the grammar and are comfortable with my gayness. Some people would have said “The main character is me,” and they do not know how to react to my strangely worded pronouncement.

To my gay self.

I inherited—yes, inherited—my grammar habit from my father. He was a stickler for grammar, too, and he often corrected my speech when I was younger. It worked—my grammar became flawless. However, I also inherited his tendency to correct other people's grammar. If, in the middle of telling a story, somebody says “Me and Kate went to the store,” I'll shove in “Kate and I” without missing a beat. The people around me will glance in my direction and then turn back toward the person telling the story, realizing that it was just Gabe, correcting grammar again. The storyteller will give me an evil look, then go on with the story. Sometimes he or she will repeat my correction and finish telling the story. Other times he or she will ignore it completely. Sometimes the speaker will deliberately repeat “Kate and me,” just to make me mad. I've learned to ignore it.

So that's what I do, I correct grammar. Do I like that I do it? No. Can I help it? No, it's just part of who I am. I deal with it.

If grammar is my gayness, then my correction of other people's grammar is my coming out, my “flaunting.” The first few times I did it, people started arguments about it. Why did I have to do that? Couldn't I just leave the grammar alone? Why did I have to shove the fact that I knew grammar well into other people's faces?

The first few times I did it, people were surprised. They didn't know what to say. I corrected grammar? I'm gay? What does this mean??

How are homosexuality and grammar even remotely alike?

People got used to it. People dealt. Now when I say that I think a guy is hot to one of my friends, the only argument I get is about my taste in guys. In fact, my gayness goes over much better than my grammar correction, which still garners a few evil looks every time I do it.

However, just as “Kate and me” or “The main character is me” have been accepted as part of our language despite the fact that they're obviously incorrect, so has it become okay to spit upon a culture, a lifestyle, a sexuality, whatever you want to call it, simply because what is right has been forgotten for what is easy. Being gay is difficult in a world that begins its sentences with conjunctions and allows participles to dangle unchecked.

Despite the wandering dependent clauses, despite the fragments passing themselves off as sentences, we're not going away.

We're here for the fight.

It's Not Confidential, I've Got Potential

by Eugenides Fico

A couple of days before my appointment, a friend and I were talking about how stuck we are in our roles as “men.” When people say we are “men,” we can hear the quotation marks in their derisive voices. What people don't seem to understand is that I'm not trying to be a man, and I'm not trying to be a “man.” I just haven't found the place between my half-man and my half-self that feels more right than this does.

My appointment was for 5:20. I was nineteen, but I hadn't had a pap test yet. Going for a pap smear is not in line with my idea of myself. It's not even in line with my idea of my half-self. But after being berated by my doctor for an entire summer, I resolved to do it. After all, pap smears are, by nature and definition, a feminine thing to do. At that point, I had spent sixteen years trying to stamp out anything that was feminine in me, and an additional three years trying to build up anything masculine. I wasn't ready to go off into the downtown of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and have someone verify, by all accounts, that there's no way I'm not a girl. Getting reminded once a month is quite enough for me.

My problem is that I don't want this “girl-thing” hanging over me. I'm caught between the effort of being a guy and the struggle to not forget where I'm from. After nineteen years of being told that I'm a girl—sixteen years of trying to equalize society's goals with my own—I can't forget that part of me. I told my friend about my appointment, about how it was a slap in the face to any alternate gender I try to create. Shim replied by saying, “The first step to recovery is admitting you have a problem.” Shim has the same problem.

We like to wear girly clothes sometimes. It's a rare occurrence, but it happens. On days like that, people invariably make “comments,” thinly veiled questions asking why the sudden change in demeanor, the change in self-expression. We invariably fall back on excuses—“I have to do my laundry.” “This was the only blue thing I could find, and I felt like blue.” “I have to meet someone's parents later.” It's not like any of these are reasons. They're almost always true, but that doesn't mean we don't enjoy the girl in us sometimes. My friend was wearing a skirt as we talked about pap tests and society and people we date and college classes. I was wearing baggy jeans and a T-shirt. It's not that we dress like men because we think we're men. We simply recognize the fact that certain parts of us are not feminine. And once we recognized this, we wanted the world to recognize it as well.

The walk over to the appointment was full of distractions. It was one of those not-quite-cool days that the Midwest seems to be full of during the fall. I had on my patched pants—pants I had spent hours sewing together after my mom serged the cloth for me. And even though the walk made me a little warm, I had worn a buttondown shirt, long-sleeved and plaid. Whenever I wear that shirt, I think of the boy in Where the Red Fern Grows, and I think of Jess from Bridge to Terabithia. I pretend that I'm some kid who grew up on a farm in the Midwest and went to college just a few hours from my hometown, rather than a girl who grew up less than a mile from the Delaware River, going to Trenton, New Jersey, for church every Sunday and driving to Philadelphia to attend folk concerts in the summer.

I never imagine that Cedar Rapids is my hometown. Growing up, we called Trenton the toxic-waste dump of the East. I make fun of Trenton with the knowledge that Trenton is a part of me. It's like when Minnesotans make fun of their own accents, or Iowans make fun of themselves for falsely being known as the Potato State. The fact that Trenton is so shitty is exactly why I love it.

Which is why Cedar Rapids can't be my hometown. It's too close to Trenton. It's like when you fall in love with someone but then break up. And then you meet someone so much like that first person that all you can do is see the differences between them. You can't love the second person in the same way or for the same reasons; you can only love them for the reasons that are different. Cedar Rapids and Trenton are the same city, which is why I always know how they're unalike. They went through the same industrial boom. They went through the same industrial desertion. There are the same ghettos and the same areas you avoid at night.

As I walked down Second Ave., a dusty old man stepped out of the brickwork, his friend having asked for some change for a phone call. Her eyes were drugged over, but I didn't see that until I was close enough to give her the money.

“How you doin'?” the guy asked me as his friend floundered for change for my bill. I fought the urge to step back as he moved closer to me. Behind me, a couple cars drove past. I answered that I was okay, that I was stressed about midterms, but whatever. I did not mention that I didn't actually have any midterms, and I was more worried about my appointment today than anything else I had coming up in the next week. “You need some weed,�

� he told me. I glanced at his friend, still counting change. There was a wide open space behind me, and neither of them was in a condition to chase me down. “No, I'm okay, really,” I said, thinking that maybe I shouldn't have stopped, that maybe I really did need to get to my appointment on time. “Naw, you need some weed.” He gave me that look, that look that says “You know what I mean, and you know that I'm right.” The friend finally finished counting. “I'm really okay,” I told him as his friend held out a palm full of coins. “It's a couple cents short. Is that okay?” I nodded. “It's fine,” I said as she handed me change with a nickel more than I deserved. I didn't bother mentioning her mistake and instead just got out of there.

I thought about who they thought I was. There's a small dilemma every time I am in a situation where I don't feel safe. My feminine training kicks in, cataloging exits and escape routes. But my masculine enforcement tries to compensate for my lack of confidence by putting on more bravado than I can hope to defend. I wonder if they noticed my giveaways. My voice is high, though it's not all that noticeable until I sing. Over the years, I've developed a slight rasp, due to hours of attempting to lower my crystalline soprano. I would take a tenor, or a countertenor. That's not asking for much. I don't need a bass or a baritone. Instead, I ended up with a high-pitched laugh and a smoker's soprano rather than a liquid-cool alto.

Walking along, I thought about how to talk at the appointment. When you lower your voice too much, people can always tell. They can tell by how fake it sounds and by the face you make as you try to do it. I was thinking that I could create an image of myself in my mind so strongly that my appointment wouldn't break me down. I just had to resolve myself. Gender is an act. All gender is an act. There's just a very big difference in people's minds about when that act is “right” and when that act is a “lie.”

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

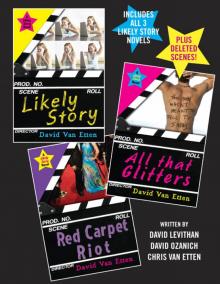

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!