- Home

- David Levithan

The Full Spectrum Page 3

The Full Spectrum Read online

Page 3

I got to the right intersection, Second Ave. and Fifteenth St. I couldn't remember the address, and I couldn't tell which side of the intersection Planned Parenthood was on. I looked at both of the possible buildings. Neither looked promising. One had a sign out front concerning realty, the other had a sign about Mount Mercy Hospital. Planned Parenthood isn't connected with the hospital, but I figured that was a better bet.

I walked in the door, hoping I didn't look like too much of an ass. There was a woman behind the desk. She was maybe fortyfive, with short hair cut very feminine and glasses low on her nose. Her hand held a bunch of papers. She gave me one of those looks, that over-the-glasses, who-the-fuck-are-you look. I wondered if she wore her glasses low in order to perfect that look. “Can I help you?” Like it was the last thing in the world she wanted to do. My mind froze a little, thinking about the fact that she probably didn't like college kids who invaded her town and walked around in grungy, patched-up pants. Thinking that she might suspect I wasn't the guy I was trying to make her think I was. I made my voice as low as possible without straining it. “I'm looking for Planned Parenthood.” She looked back at her papers. “Across the street and around the back.” There was no sincerity in my voice when I said thanks and walked back out. The defiant teenager part of me hoped she'd make assumptions about me while I wasn't there to defend myself, just because I knew she was wrong. The transgendered part of me hoped those assumptions would involve me having a pregnant girlfriend.

There was a canopy hanging out behind the realty building. I walked under it and opened one of the glass double doors. I found another set of doors around a corner, clearly labeled Planned Parenthood of East Central Iowa. I walked in and stopped, surveying the scene. Women sat in chairs, comfortable in this waiting room. Some children played with toys that had been provided. The women and children stared at me. I lost my focus and glanced around the rest of the room. There's a difference between glancing and surveying, although most people don't notice it. There's a difference between looking nervous and looking like you're used to being in control; people always notice that. Glancing never implies control.

I told a friend of mine about it later, how everyone stared at me when I walked in. He's a farmboy from Charles City. “That's Iowa,” he said. “That's what we do. When someone walks into the room, we look at them to see if there's any way we know them.” In Pennsylvania, a glance is customary, but nothing more. For men, a swift perusal is what is required. In that look, we assess whether we know the person or not, and we make our initial judgments. And one of the most important judgments is whether the person is a guy or a girl. With nine pairs of women's and children's eyes staring at me, they must surely have realized the physical fact I was trying to hide.

I walked up to the counter, trying to regain my control. I told the receptionist why I was there, trying not to let everyone else in the room know as well.

Half an hour later, having completed page after page of paperwork, I was in a private room, sitting in one of those mass-produced chairs that still manages to be semi-comfortable. A woman came in. I made a conscious effort to keep my head up and not fidget. She had papers in front of her, the ones I had filled out minutes before. As she looked them over, she asked me questions, clarifying where my words had been insufficient.

“You're on birth control?”

“I went on because I got my period for five and a half weeks out of eight,” I said.

She winced sympathetically and asked what kind of birth control it was. Reaching into my backpack, I handed her the package. She nodded and handed me a prescription, saying she had prescribed me for one year.

“You've had sexual relations with both men and women?” I was impressed by how nonjudgmental she sounded. Iowa has gotten me on my toes.

“Yeah, but the last person I dated was a girl, and we didn't have sex.” She wrote something down.

“Have you had sex?”

I paused, unsure how to proceed. I had known this would come up. But I had just forced myself to come to the appointment without thinking. If I don't think about things, I can't get scared enough to back out.

“Well,” I said, “see, when I was younger, there was this older boy in my neighborhood.” I was looking at a picture on the wall; it reminded me of the teeth pictures I always see at the dentist, the ones that show gingivitis. “I don't think I've ever had sex, but I kind of blocked out some of what happened.” I wasn't looking at her; the picture on the wall depicted a cervix. “So I'm not exactly sure.” I should have stopped talking there, but I kept going. “That was actually part of why I wanted to come. Because I don't think I have AIDS or anything, but there's always a chance.” She nodded, looking at me. Maybe I didn't actually say those last thoughts. I tend to misremember things, imagining I've said something I thought about. I can't remember the rest of our conversation. I just remember thinking to myself, She's the fourth person to know.

I have a habit of being unaffected by things, but I think things must affect me more than I know. It's just a question of what I'm willing to admit to myself. When I think about having sex with a guy, it weirds me out. I can't imagine trusting someone that much. But thinking about having sex with a girl makes sense, like I was vaguely meant to play that role. Philosophers have this theory called Compatibility Theory. It's the idea that a man and a woman are meant for each other because they complement each other. The theory states that men and women are opposite, and opposites attract. Maybe the theory is right. Maybe I'm an opposite of women because I was born one, the same way Cedar Rapids is Trenton's opposite because of the differences they have, differences I only notice because of their similarities.

The woman sitting with me, maybe her name was Susan, didn't seem interested in whether or not I was compatible with The Boy, and she didn't seem to care whether or not I was compatible with either of my girlfriends. She was more interested in whether I was at risk for AIDS and whether my siblings had genetic-related diseases. I appreciated how she did that.

I didn't think much during the examination. Susan explained everything before she did it, warning me of what was coming. Despite this, I wasn't ready. I had spent the past two weeks thinking I knew what a pap smear would be like, but the actuality was nothing like my preconceived notions.

I left half an hour later, the feeling of invasion making me wince a little with every other step. It didn't hurt to walk, but rather it hurt to know someone had known parts of me even I didn't know directly. Susan had asked me to take off my clothes and put on the paper gown, shutting the door behind her. The gown was pink. It was strangely warm against my skin. It reminded me of when I learned how much heat newspapers can hold. When she came back, her professional hands took over, the same as her professional words had taken control during our discussion. I've based so much of my gender identity on my body. My identity is fundamentally related to the idea that, because of how I was born, people don't treat me the way I would like to be treated. The pap smear touched where I had hidden my identity, breaking the barrier I had tried to create on my walk. It wasn't so much the invasion of my vagina as the invasion of my self.

People often assume I hate my vagina, that I would rather have been born male and be done with it. They're all wrong. I remember when I was younger, I suffered from the same syndrome Pinocchio did. I thought I could grow up and have a sex-change and become a “real” boy. Now that I'm older, I can't have a sex-change because that would mean sacrificing the personalities I've tried to become. People who move from one sex to the other are required to destroy their previous lives. There's a home video of my family at Christmas when I was nine years old. I got makeup from my grandmother, and I ran around the house excited to have it. I don't remember this, but it's important to me that it happened. It's central to my idea of myself, the fact that I found makeup important when I was that age. I can't have a sex-change because sex isn't the problem. The problem is that people are too intent to categorize me as a person who enjoys shopping and m

akeup and boys, simply because I look a certain way.

At this point, the stereotypes people hold for me don't include shopping or boys. They hold the opposite. It's assumed that I know about sports teams and cars and that I only want to date girls. My gender is an act, but acting is open to interpretation. People see me the way they are comfortable seeing people. I'm “the gay girl” on campus because that's who people can handle me being. On the rare day that I wear girly clothes, people do a double take. They say, “Gen! You look good.” Other days, I simply look like the person they've learned to see me as. I don't say I have to do my laundry because I'm embarrassed that I sometimes like tight shirts and flare pants. I say it because, in their minds, by admitting that I sometimes enjoy the girl in me, I admit that I'm not a man.

A couple months after the pap, I went to a different town, where no one knew me. I wore a beard, applied with spirit gum and my own hair. People asked a friend about me, seeing me for the “man” I was trying to hide. I try to be a man for the same reasons I say I have to do my laundry. By taking anything less, I take on the role of not-man. And the only other role society will recognize is woman.

Snow and Hot Asphalt

by Benjamin Zumsteg

Conversations about where I grew up can go one of two ways. When pressed for time, I say I grew up in Chicago. Mostly.

I do this on purpose, hoping that I don't have to explain. If I do, I have to involve my arms in back-and-forth movements, explaining the two points in my life in which I lived in Utah. When that comes up, I get the usual response. They ask, “How did you survive that?” or “Isn't it boring?” or “What about those crazy Mormons?”

I explain what I can, trying to keep things short and simple. And each time, the same image comes to my mind in a flash of hot light.

In that image, it is late August and I am stepping out of my mother's forest-green minivan. I am in the middle of a Brigham Young University parking lot in Provo, Utah, waiting for my mother to finish some meetings. It is the week before her first year of teaching. The car is not on, but I leave the key in the ignition and let my music play in the tape player loudly, speaking my mind to the rows of baking sheet metal. I'm gonna do my best swan dive, the speakers sing, into shark-infested waters….

I step out of the car for some fresh air, though “fresh” is a relative term. It is stiflingly hot outside. My lips crack as I squint into the sun. I have just begun the drying-out process that comes with moving to a desert.

I look down at the newish black asphalt, marked with winding strips of tar. I squish my flip-flop down into it with one foot, turning it inward, twisting the tar around. I release the pressure and it pops back into place as it unsticks itself from the ball of my foot.

I look up, facing east. I am met with a towering wall of mountains. From my current vantage point I am forced to look up to get the full, panoramic view. Directly ahead of me, still technically in the foothills, brush and trees dot the dull khaki-colored grasses with shades of olive. My eyes move upward, along the slithering grooves in the hillsides, as the packs of trees become thicker and thicker, coated in a deep, rich green.

My view reaches the tops of a few of the highest mountains and I see that there is still snow. It is an observation I have often taken for granted; the illustrated image of a mountain always consists of that tiny, squiggly line drawn across the top.

The whites of these caps throb in the light. This snow lives on in the hot months. It stays cool at that altitude, even as the sun beats down on it. Small glaciers in the mountain valleys keep their poise and move slowly, steadily, as they carve out their paths behind the mountain faces. Small pools dot the places where the glaciers once squatted on the landscape. Dense fields of wildflowers in orange, purple, blue, and yellow surround the pools, tucked into small valleys within the mountains.

I see none of that. I am down on the sticky asphalt while the snow shines on.

I don't ever tell anyone about that image, though. It is only what flashes through my mind as I tell them bits and pieces, as I tell them that no, I couldn't have eighteen boyfriends in Utah and that the beer really isn't weaker. But that image is permanent, burned into my eyes as I tell them the small details.

If they have time, and if I feel up to it, I tell them a little more.

I arrived in Utah from Chicago, where I had grown up. I was born in Utah sixteen years previously, but I called myself a Chicagoan. The flat, sometimes rolling land of Illinois was home to me, the way Lake Michigan taught me which way was east. The tight suburban roads of Chicago were comfortable. Utah's mountains had always been a backdrop for Christmas and summer vacations, a reason to say “I miss the mountains,” but otherwise they'd remained a distant, lofty memory.

Though everyone in Chicago knew I was Mormon, I had ways of escaping it, especially as I came to terms with the fact that I was gay. I could confide in small groups of friends at school; I escaped for several hours a day at figure skating practice and for weeks on end at competitions. I could go days without seeing another Mormon except for my mother, and she was enough.

The unraveling of our relationship as mother and son, which had taken place two summers earlier, was somewhat distant at the time of our move. The secrecy of my first gay friendships, the subsequent tearful confession, and the hard-nosed surveillance that entrenched us in battle was something we didn't often speak about. However, my mother couldn't shake the feeling that I had betrayed her. In some ways, the news that I had consistently lied to her about my life was worse than the actual “problem” of my homosexuality.

Despite all this, I felt the need to keep going in this new life I was seeking out. I would still sneak off to meet gay friends while my mother worked at a library and taught her students and performed freelance gigs. Sometimes she dragged me with her to wherever she was going because she didn't trust me. She had every right not to. We could go long stretches of time without saying anything about it, but who I had become or the “choice” I was making managed to put a damper on any interaction we had.

In moving us back to Utah, my mother had new hope. She was returning to a position she had held at BYU when I was born. It was a full-time position that she actually wanted instead of working a day job to support her real passion. It was a secure, larger income in a state with a lower cost of living.

My mother held out hope that a return to the physical center of Mormon culture would influence my life. I would be going to a predominantly Mormon high school, going to church only with people who lived within two blocks of me, and living only minutes from a university that was home to over 20,000 Mormons. They were everywhere, and she thought this was a good thing.

I dreaded it. My mother accepted the position six months before it started and bought a house, sight unseen, five months before we even moved. I prepared to say goodbye to friendships that had just begun to develop in all my worlds: high school, skating, and the gay world my mother forbade me from existing in. That world, the one I still knew the least, was the hardest for me to leave behind.

I had been warned about Utah and about Provo, where I'd be living, in particular. The place was 80 percent Mormon, but strong percentages didn't necessarily mean strong faith. The bishop of my congregation before I left Chicago warned me of this, telling me that I'd see more hypocrisy amongst kids my age there than I ever did here. This was news to me, considering that one of the guys my age in my congregation had been flirting with me for about two years and several more were heavy drinkers.

After a long goodbye to Chicago, I was on that hot pavement in a parking lot at BYU, waiting for my mother to finish with her obligations. It was a scene I would repeat countless times over the course of my time in Provo; I'd sit in the car, music blaring, until she would walk out, cello usually in hand, and I would turn the music down, get out of the car, and help her with the instrument's bulky case. At her concerts in Chicago, I hauled her cello everywhere. She called me her roadie. My dutiful position had not ended with the move.

A year after I arrived in Utah, I was invited to go on a hiking trip with my congregation's youth group. I was less than thrilled, especially because it meant waking at five in the morning. We had to get an early start because it was still August and the days got very hot very quickly. We were to climb Mt. Timpanogos, the highest peak in Utah Valley at just over 11,000 feet. We would not climb to the summit, however, but to a point called Emerald Lake, which was a few hundred feet below the steep ascent to the top.

Local Indian legend (as I read on a plaque in a local Mexican restaurant) told of how “Timp” is shaped like a dead maiden, lying flat on her funeral bed, with the jagged peaks forming her feet, clasped hands, chest, and disproportionately large nose. The steep slope bridging Timp with the other mountains to the south tumbles down into a canyon and is said to be the warrior who grieves her death, clasping his hands against her head, his cape dropping to the valley floor.

I didn't mind the hike so much once we got going. What annoyed me most were the occasional stops to read an inspiring scripture passage to keep us going. The day continued to get warmer as we ascended, stopping for inspiring thought after inspiring thought. During those times, I either looked down at the ground below us or at how impossibly high the ascent looked above us, not paying attention to what was being said. We continued upward; we walked up through switchbacks in the massive wall behind the mountain as the day wore on, stopping to let others catch up. I stayed at the front of the pack, not caring to look back.

Adjusting to my new high school, Timpview High, was not unlike adjusting to a climb. It was just as bothersome and persistent as the dry, cracked skin I was constantly trying to hydrate. It left me as exhausted as the altitude did. In Provo, even a short run, every quick burst of energy, left me nearly breathless.

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

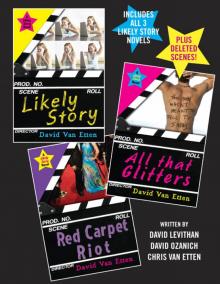

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!