- Home

- David Levithan

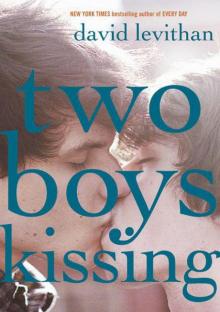

Two Boys Kissing Page 2

Two Boys Kissing Read online

Page 2

They are at Harry’s house. His parents are out for the night, the dog already asleep. Because the house feels theirs, the world feels theirs. Why would you want to close your eyes to that?

They are at Harry’s house because Craig’s parents can’t know about the kiss. At some point they will. But not now. Not before it’s happened.

Eventually Harry will leave Craig curled on the couch. He will tuck Craig in, then tiptoe back to his own room. They will be in separate places, but they will have very similar dreams.

We miss the sensation of being tucked in, just as we miss the sensation of being that hovering angel, pulling the blanket over his shoulders, wishing him a sweet night. Those are the beds we want to remember.

We are excited for the kiss tomorrow. We don’t see how they can do it, but we are hoping they will.

Pink-haired Avery was born a boy that the rest of the world saw as a girl. We can understand what that’s like, to be seen as something that you are not. But for us it was easier to hide. For Avery, there is a thicker chain of biology to break. At a young age, his parents realized what was wrong. His mother thought that maybe she’d always known, which was why she’d chosen the name Avery—her father’s name, which was going to be given to the baby whether it was a boy or a girl. With his parents’ help and blessing, if not always comprehension, Avery charted a new life, was driven many miles—not to dance or drink, but to get the hormones that would set his body in the right direction. And it’s worked. We look at Avery now and know it’s worked, and appreciate the marvel of it. In our day he would have been trapped by an insurmountable body in an intractable world.

As they’re dancing, Avery wonders if Ryan realizes, and worries that Ryan will care. The blue-haired boy sees him—this is for sure. But does he see everything, or only what he wants to be seeing? This is always one of the great questions of love.

Ryan is more worried by time, and what to do about time. He cannot believe he’s found someone here in the bowels of the Kindling community center. The same place he learned to swim. The same place he took rec-league basketball when he was nine. The same place he’s staffed bake sales and blood drives and the same place he’ll vote, when he’s old enough to vote. Yes, it’s also the same place he ducked out of to have his first cigarette and, a couple of years later, his first joint, but it’s never been somewhere he would have imagined finding a pink-haired boy to dance with. He can sense his friends watching from the sidelines, whispering about what will happen next. This only amplifies his own need to know. Time is running out, but what is it running toward? Should he stop and talk to this boy more, before the DJ plays the last song and the lights come back on? Or should they stay like this, paired by the music, cocooned in a song?

Talk to him, we want to say. Because, yes, time can be buoyed by wordlessness, but it needs to be anchored in words.

We know what their best chance is, and in this, the DJ does not disappoint. As most DJs will at some point in an evening, he spins a song that means a lot to him and nothing to anyone else present. Within seconds, the floor starts to clear. Conversations rise from a buzz to a clamor. A line forms at the men’s room.

Both Avery and Ryan stop. Neither wants to leave if the other wants to stay.

Finally, Avery says, “I can’t see any way to dance to this song,” and Ryan says, “Do you want to get some water?”

An escape is made.

The DJ opens his eyes and sees what he’s done. By all rights, he should switch the song. But it’s a long-distance dedication to the boy he loves down in Texas. He dials up the boy right now and holds his phone into the air.

Not all songs need to be for dancing. There will always be the next song, to draw the dancers back.

This is what happens when you become very ill: Dancing stops being a reality and becomes a metaphor. More often than not, it is an unkind one. I am dancing as fast as I can. As if the disease is the fiddler who keeps playing faster and faster, and to lose step is to die. You try and try and try, until finally the fiddler wears you down.

This is not the kind of dancing you want to remember. You’ll want to remember a slow song like Avery and Ryan’s last dance. You’ll want to remember dancing as Tariq remembers dancing, as he heads home from his night at the club. It’s only eleven at night—which is barely noon when you’re on party time—but he promised Craig and Harry that he’d get some sleep, so he can be with them for the big kiss tomorrow without nodding off. It was hard for him to step away from the music, from the pulse it created. He tries to simulate it now by blasting music in his ears, ignoring the other sounds on the late-night suburban train. It’s not the same, because there are no other boys to look at or to be looked at by, just remnant commuters and some girls who’ve just seen some Broadway show. One of them tried to catch Tariq’s eye earlier, and he just gave her a nice try, sorry smile, sending her back into her Playbill.

If you close your eyes, you can conjure a world. Tariq closes his eyes and sees butterflies. The vibrancy of them, spinning in the air to the music in his mind’s eye. That’s who he wants to be—on the dance floor and in life. A butterfly. Colorful and soaring.

There is something about the pureness of butterfly dreams, about all the things that dancing can unlock when you are young. When it works, that freedom doesn’t stop when the last song is played. You take it with you. You use it for bigger things.

You notice when it’s taken away.

Ryan and Avery can feel their words working with each other, can feel the simple joy of falling into the same rhythm, thinking companionable thoughts. Ryan’s friend Alicia is giving him a ride home, and she is hovering on the periphery, shooting him a look every now and then. Ryan ignores this, because he and Avery are in their fortress of non-solitude, talking about how small their towns are and how strange it is to be at a gay prom. Ryan loves the way Avery’s hair swoops, loves the shy curiosity in his eyes. Avery, meanwhile, keeps stealing peeks at the tip of Ryan’s V-neck, at his jeans, at his perfect hands.

We remember what it was like to meet someone new. We remember what it was like to grant someone possibility. You look out from your own world and then you step into his, not really knowing what you’ll find there, but hoping it will be something good. Both Ryan and Avery are doing this. You step into his world and you don’t even realize your loneliness is missing. You’ve left it behind, and you don’t notice because you have no desire to turn back.

You keep your eye on him.

Perhaps because of the Diet Dr Pepper consumed earlier, Peter and Neil are up later than they expected to be. The date was a success, even though they’ve been together long enough that they don’t even think of it as a date, just as a night together. They watched both movies in quick succession—horror first (for Neil), then romantic comedy (for Peter), with Neil holding himself back from smiling at Peter’s fright during the horror and his tears as the romantic comedy resolved itself in predictable romantic comedy fashion. Peter is still self-conscious about these things, and Neil is conscious of this self-consciousness … even if he can’t always contain his amusement. (“Are you all right?” he asked at a moment during the romantic comedy when Peter seemed particularly tense, and he couldn’t help but squeeze Peter’s arm with mock sympathy when Peter said, “I just want Emma Stone to be okay.”)

Neither of their sets of parents are ready for sleepovers yet, so Neil left Peter’s house a stroke before midnight, and now they are in their own rooms in their own houses, talking to each other over the Internet as they each get ready for bed. Every now and then one of Neil’s Korean relatives pops up in the Skype column, and Neil is relieved that none of them attempt to say hi. Peter’s connection is devoted solely to Neil, at least at this hour.

Peter thinks there is nothing more adorable in the whole universe than the sight of Neil in his pajamas. They are proper pajamas—striped button-down shirt with matching striped elastic-waisted bottoms. They are at least a size too big, and make him look like he’s wa

iting for Mary Poppins to pop her head in and say it’s time to go to bed. Peter is in boxers and a T-shirt that reads LEGALIZE GAY. Even though they’ve just spent hours talking, they spend another hour talking, sometimes sitting at their computers and looking at each other, and other times letting the cams gaze on as they walk around their rooms, brush their teeth, pick out clothes for tomorrow. We envy such intimacy.

There comes a point where Peter and Neil’s conversation becomes too cloudy to continue. Even Diet Dr Pepper wears off after a while. But their cloudiness is the white, puffy kind, the kind of clouds that little children imagine will carry them off to sleep. Peter wishes Neil sweet dreams, and Neil wishes the same thing back. Then, for just a moment, they wave to each other. Smile. One last glimpse of pajamas, then goodnight.

Eventually, we all must go to sleep. This is our first intimation that the body always wins. No matter how happy we are, no matter how much we want our night to stretch out infinitely, sleep is inevitable. You might be able to dodge it for one giddy cycle, but the body’s need will always return.

We used to fight it. Whether our allegiance was to talking in the dark or to dancing in the flashing lights, we wanted our nights to be endless. So the conversation could continue, so the dance could push on. We’d fill ourselves with coffee, with sugar, with stronger, more dangerous substances. But drowsiness would always tug at our tide, and eventually turn it.

We would playfully think of sleep as the enemy, the scourge. Why reside in the house of sleep when there was so much going on outside of it? And then the fight became more desperate. When you know you only have months left, days left, who wants to sleep? Only when the pain is too much. Only when you are desperate for the negation. Otherwise, sleep is time you’ve lost and are never getting back.

But what a pleasant negation it is. Drifting over the land of sleep and dreams, we can see why insomniacs beg and dreamers lead. We watch Craig curled on Harry’s lime-green couch, under an afghan that Craig’s great-grandmother crocheted. We watch Harry in his bedroom, his arms rounded and his hands beneath his head, his body a lowercase q. In another corner of the same town, Tariq has fallen asleep with headphones on, Icelandic music looping through his nighttime travels. In another town, Neil in his pajamas dreams that he and Peter are playing tic-tac-toe, while Peter in his T-shirt and boxers dreams that emperor penguins have taken over the local mall and are trying to sell sunglasses to Emma Stone. Back in a town called Marigold, Avery falls asleep with a phone number written on his hand, while in a town called Kindling, Ryan has taken a sleeping bag and has fallen asleep under the stars, smiling at the thought of a pink-haired boy and what they might do tomorrow.

Only Cooper is still awake, but that won’t last long. He types himself into other time zones, talks with men who are just waking up, men who are sneaking a moment from work. He deceives them all, but cannot deceive himself. He is still nowhere, and no matter how hard he looks, there’s no somewhere to be found, especially inside of himself. He believes the world is full of stupid, desperate people, and he can only feel stupid and desperate to spend so much time with them. We are worried by this. We tell him to go to sleep. Everything is better after sleep. But he can’t hear us. He goes on and on. His eyes start to close more and more. Go to bed, Cooper, we whisper. Go to your bed.

He falls asleep at the computer. Men from other hours ask him if he’s still there, if he’s gone. Then they move on to newer windows, leaving Cooper’s empty. He cannot notice when everyone else has left the room.

This is an incomplete picture. There are boys lying awake, hating themselves. There are boys screwing for the right reasons and boys screwing for the wrong ones. There are boys sleeping on benches and under bridges, and luckier unlucky boys sleeping in shelters, which feel like safety but not like home. There are boys so enraptured by love that they can’t get their hearts to slow down enough to get some rest, and other boys so damaged by love that they can’t stop picking at their pain. There are boys who clutch secrets at night in the same way they clutch denial in the day. There are boys who do not think of themselves at all when they dream. There are boys who will be woken in the night. There are boys who fall asleep with phones to their ears.

And men. There are men who do all of these things. And there are some men, fewer and fewer, who fall to bed and think of us. In their dreams, we are still by their side. In their nightmares, we are still dying. In the blurriness of night, they reach for us. They say our names in their sleep. To us, this is the most meaningful, most heartbreaking sound we ever had the privilege and misfortune to know. We whisper their names back to them. And in their dreams, maybe they hear.

We wish we could show you the world as it sleeps. Then you’d never have any doubt about how similar, how trusting, how astounding and vulnerable we all are.

We no longer sleep, and because we no longer sleep, we no longer dream. Instead we watch. We don’t want to miss a thing.

You have become our dreaming.

In the middle of the night, Harry’s mother opens his door, checks that he’s safely asleep. Then she heads to the den and does the same for Craig, smiling to see him wrapped in the afghan. She knows they have a big day tomorrow, and she is worried for them. But she will only show her worry when they are asleep. Mostly she is proud. Pride is allowed to have an element of worry, especially when you are a mother.

Harry’s mother tucks him in for a second time. She kisses him lightly on the forehead, then tiptoes from the room.

We miss our mothers. We understand them so much more now.

And those of us who had children miss our children. We watch them grow, with sadness and amazement and fear. We have stepped away, but not entirely away. They know this. They sense it. We are no longer here, but we are not yet gone. And we will be like that for the rest of their lives.

We watch, and they surprise us.

We watch, and they surpass us.

The music in Tariq’s ears fades, the battery diminished. He doesn’t notice. It is one of the body’s greater gifts, the ability to prolong music long after it’s faded from the air.

Asleep in his backyard, Ryan does not notice the halo of dew that gathers around him as the night warms into morning. His eyes will open to a sparkle on the grass.

The waking world. Even the most cynical among us must greet it with a touch of hope. Maybe it’s a chemical reaction, our thoughts communing with the sunrise and creating that brief, intense faith in newness.

We fall quiet as we watch the sun reach over the horizon. No matter where we are, no matter who we’re watching, we pause. Sometimes we look to the distance to see the dawning of the day. And other times we witness it as it’s reflected on the people we’ve come to care about, watch as the light spreads over their sleeping features. How can you not hope as the world, for an instant, glows gold? We, who can no longer feel, still feel it, the memory is so strong.

Waking is hard, and waking is glorious. We watch as you stir, then as you stumble out of your beds. We know that gratitude is the last thing on your mind. But you should be grateful.

You’ve made it to another day.

Harry wakes up excited. Today is the day. After all the planning, after all the practice. This particular Saturday is no longer a square on the calendar. It is no longer a date talked about in future tense. It is a day, arriving like any other day, but not feeling like any day that has come before.

He goes straight from his bed to the kitchen—moppy hair askew, clothes sleepworn—and finds his parents there, gearing up in their way for his day. His dad is making breakfast and his mom is at the kitchen table, reading the crossword clues out loud so the puzzle can be filled in together.

“We were just about to wake you,” his mother says.

Harry keeps walking to the den. Craig is sitting bolt upright on the couch, looking like the morning is a mathematical problem he needs to solve before he gets out of bed.

“Dad’s making French toast,” Harry says, knowing the additio

n of food to the equation will help it get solved faster.

Craig responds with something that sounds like “Muh.”

Harry pats him on the foot and heads back to the kitchen.

Tariq’s alarm goes off, but he doesn’t feel alarmed. With his headphones still dulling the outside noise, it sounds like there’s music coming from the next room, and he takes it, slowly, as an invitation.

As soon as Neil is out of the shower, he texts Peter.

You up? he asks.

And the reply comes instantly:

For anything.

We smile at this, but then we look over to Cooper’s house and we stop. He is still asleep at his desk, his face just barely glancing the keyboard, keeping the computer awake through the night. His father is coming into the room, and he doesn’t look happy. All of Cooper’s chat windows are still on the screen.

We shiver in recognition at what’s about to happen. We see it on his father’s face. Who among us hasn’t done what Cooper’s just done? That one mistake. That stupid slip. The magazine left spread-eagled on the floor. The love notes hidden under the mattress, the most obvious place. The torn-out underwear ad folded into the dictionary, destined to fall out when the dictionary is opened. The doodles we should have burned. The writing of another boy’s name, over and over, over and over. The clothes shoved in the back of our closet. The book by James Baldwin sitting on our shelf, wearing another book’s jacket. Walt Whitman beneath our pillow. A snapshot of the boy we love, grinning, the conspiracy of us in his eyes. A snapshot of the boy we love who has no idea that we love him, captured oblivious, not knowing the camera was there. A snapshot we kept in our top desk drawer, in a fold in our wallet, in a pocket next to our heart. We should have remembered to take it out before throwing it in the laundry hamper. We should have known what would happen when our mother opened the drawer, looking for a pencil. He’s just a friend, we’d argue. But if he was just a friend, why was he hidden, why were we so upset to have him discovered?

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

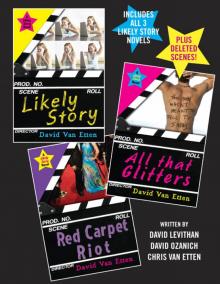

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!