- Home

- David Levithan

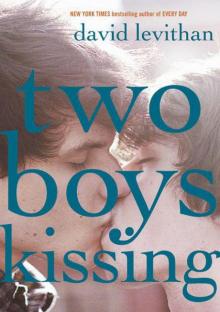

Two Boys Kissing Page 3

Two Boys Kissing Read online

Page 3

We want to wake Cooper up. We want to make the door louder as it opens. We want his father’s footsteps to sound like thunder, but instead they sound like lightning. His father knows how to do this, his anger building quiet speed. He leans over his son and reads the remnants of last night’s conversations. Some are merely conversational, a bored patois. What’s up? Not much. U? Not much. But others are frank, sexual, explicit. Here’s what I’d do to you. Is that the way you want it? We look closely, hoping for concern to spread over the father’s face. Concern is okay. Concern is understandable. But we, who have looked so long for signs of concern in others, see only disgust. Revulsion.

“Wake up,” the father says.

Anger. Rage.

When Cooper doesn’t stir, he says it again and kicks Cooper’s chair.

That does it.

Cooper jolts awake, his face pressing into the keyboard, creating an unsayable word. His contact lenses feel like dry wafers on his eyes. His breath tastes like morning worms.

His father kicks his chair again.

“Is this what you do?” is the angry accusation. “When we’re asleep. Is this what you’re up to?”

Cooper doesn’t understand at first. Then he raises his head, swallows the meager spit in his mouth, sees the screen. Quickly, he closes the laptop. But it’s too late.

“Is this what you do in my house? Is this what you do to your mother and me?”

From a cold distance, we know that confusion is at the heart of this disgust. And into that heart is pumping a steady flow of hate and ignorance.

We know that Cooper doesn’t have a chance.

His father grabs him by the shirt and pulls him up, so he can be screamed at eye to eye.

“What are you? How could you do this?”

Cooper doesn’t know. He doesn’t know what to say. He doesn’t know what to do. There aren’t even answers.

The father’s face is burning red now. “Do you just go off and fuck men? Is that it? While we’re asleep, you go out and fuck them?”

“No,” Cooper finally says. “No!”

“Then what is this?” A disgusted gesture to the closed computer. “What kind of whore are you?”

Fuck. Whore. These are not words any son should hear from his father. But the father’s rage has its own language. It does not have to talk like a father.

“Stop,” Cooper whispers, tears filling his eyes. “Just stop.”

But there is no stopping. Cooper’s father pushes him against the wall. Impact. The wall shakes and things fall. Cooper is no longer nowhere. He is somewhere now. And it is a horror. It is everything he never wanted to happen, and it’s happening.

His mother comes running into the room. For a moment we are grateful. For a moment, we think it will stop. But the father doesn’t care. He keeps yelling. Faggot. Disgrace. Whore. Sick.

“What’s going on?” the mother yells. “What’s going on?”

Cooper cannot stop crying, which makes his father even angrier. And now his father is explaining to his mother. “He sells himself to men on the Internet.”

“No,” Cooper says. “It’s not like that at all.”

“Open it,” his father commands his mother. “Read.”

Cooper actually lunges, tries to grab the laptop away. But his father knocks him back, pins him down as his mother opens the computer. The screen lights up. She begins to read.

“It’s just chatting,” Cooper tries to tell her. “Nothing ever happens.”

But the look on her face as she reads … some of us have to turn away. We know that look. Something inside her is breaking. And in that breakage, she is giving up on us.

There is nothing more painful than watching someone give up on you. Especially if it’s your mother.

Some mothers recover from this moment. Some never do. And within the moment, the trouble is: You can’t know which way it will go.

“You see,” the father says.

A fuse in Cooper finally reaches the explosive core, detonates. He has to stop this. He has to do something. He doesn’t mean for it to be fighting back, although later it will look like fighting back. All he wants is for his mother to stop reading. So he jumps for the computer, tears it from her hands. In surprise, she recoils, and his father is too unprepared to catch him. But even though Cooper’s gotten it out of her hands, it won’t stay in his. He fumbles, and the laptop goes crashing to the floor, making a terrible sound. He reaches down and picks it up, but now his father is on him, pulling at his back, spinning him around. Cooper knows the blow is coming, and he lifts the laptop to block it. His father’s fist is too fast, and it slams into his cheek before he can get the laptop up. “No!” his mother cries out. She gets in between them—she will do that much. Cooper doesn’t hesitate. His keys and his phone are in his pocket. So he runs. He runs out of the room as his father rages behind him—raging at him, raging at his mother. He runs out the front door, runs to his car. He sees his parents coming after him, hears his father screaming but doesn’t understand the words. When he turns the car on, the music blasts. He doesn’t check to see if any cars are coming as he pulls out of the driveway, even though he knows this will only piss off his father more.

It only takes him ten seconds to leave his parents.

Besides strangers, they are now the only people in the world who know he’s gay.

You spend so much time, so much effort, trying to hold yourself together.

And then everything falls apart anyway.

In the time it takes for all of this to happen, Tariq takes a shower. In the time it takes for all of this to happen, Craig (admittedly a slow eater) eats a piece of French toast. In the time it takes for all of this to happen, Peter loads up a video game and starts to play. In the time it takes for all of this to happen, Avery wakes to find a phone number still written on his hand, and wonders what to do next. He doesn’t have to worry, though. Ryan is already on it. He has Avery’s number in his phone, and as soon as the clock hits ten, he’s going to call. He feels it’s rude to call anyone before ten. So he waits. Impatiently, he waits.

It’s funny the things you miss. Like phone cords.

Reading this today, you might not even know what a phone cord is. Or it’s a relic that you see in an office, or on that antique phone in the corner of the classroom, used to call the principal’s secretary.

But once upon a time—that would be our time—a telephone cord seemed like nothing less than a lifeline. It was your attachment to the outside world and, even more than that, your attachment to the people you loved, or wanted to love, or tried to love. Everything about it was fitting—the way it curled in on itself, they way it got so easily tangled, the way you could pull it only so far before it kept you in place. Twisted and knotted and essential. It kept us tethered to each other, tethered to all the questions and some of the answers, tethered to the idea that we could be somewhere other than our rooms, our homes, our towns. We couldn’t escape, but our voices could travel.

When the phone didn’t ring, it mocked us.

When the phone rang, we clutched at it, grateful.

At precisely ten o’clock, Avery’s phone rings. Avery doesn’t recognize the number, then checks it against his hand.

“Hello?” he says.

“Hi,” Ryan says, as happy to be heard as Avery is happy to hear him.

They begin to make plans, and a plan. Plans are the things you are going to do at a precise time, while a plan is the more general idea of all the things you might do together. Plans are the coordinates; a plan is the entire map. Plans are the things you can discuss in that first nervous phone call. A plan is the thing that goes unsaid, but puts the hope in your voice nonetheless. While Avery and Ryan figure out what they are going to do today, the word together becomes the plan underlying the plans.

Avery knows his parents will give him the keys to the car again. So he volunteers to return to Kindling, to see what it has to offer. Ryan tells him it isn’t very much, but Avery is experi

enced enough in his flirtations to say that as long as Ryan is there, it will be enough.

When Avery hangs up the phone, he smiles. When Ryan hangs up the phone, he panics. Buoyant objects still exert pressure. Ryan wants to clean his room, clean his hair, clean his life, clean his town all at once.

Avery, meanwhile, smiles his way to the shower. There are things for him to worry about, too, for sure. But those beasts are polite enough to wait at the gate until he makes his preparations.

There is nothing so heartening as a chance.

You will never forget what that feels like, that hope. Yes, we could talk to you for days on end about all the bad first dates. Those are stories. Funny stories. Awkward stories. Stories we love to share, because by sharing them, we get something out of the hour or two we wasted on the wrong person. But that’s all bad first dates are: short stories. Good first dates are more than short stories. They are first chapters. On a good first date, everything is springtime.

And when a good first date becomes a good relationship, the springtime lingers. Even after it’s over, there can be springtime.

A lot of thought has gone into the location of Craig and Harry’s kiss.

If convenience had been the deciding factor, the obvious choice would have been to do it in Harry’s house, or in his backyard. The Ramirezes would have been more than okay with this, and would have made all the arrangements that needed to be made. But Craig and Harry didn’t want to hide it away. The meaning of this kiss would come from sharing it with other people.

It was Craig who suggested the lawn in front of their high school. It was public, but also familiar. The school itself was usually open on weekends for one reason or another—a football game, play practice, a debate tournament. But on the lawn, they wouldn’t be in anyone’s way. There was plenty of access to water and electricity. And their friends would know where to find them.

They debated over whether to ask permission. Harry’s parents insisted on it. Harry and Craig made an appointment with the principal and explained their kiss to her.

She was sympathetic. Almost surprisingly so. She gave her permission, but warned them that there were still risks.

They accepted that.

Now here they are, pulling into the empty high school parking lot. Football won’t happen until tomorrow, and play practice doesn’t begin until two. The building has earned its indifference on this Saturday morning. It has seen many worse things than two boys kissing.

Smita, Craig’s best friend, is already there waiting. She thinks Harry and Craig are crazy for doing this, and that of the two of them, Craig is the crazier one. Because, she thinks with only mild hyperbole, his parents are going to kill him. And if his parents don’t, maybe kissing Harry will. Because when it all comes down to it, the breakup was much easier for Harry than it was for Craig. In Smita’s eyes, Harry got off easy. He got to feel it was mutual. And then he got to go on with his life while Craig spent the next year still in love with him.

Okay, maybe not a full year. Smita isn’t very good with relationship math. (Who is?) The point is, it was long enough. Too long. And even though Craig tells her up and down and back again that he’s totally over Harry, that they’re just friends now, and even though she’s learned not to contradict him out loud, just to lay the groundwork so he can come to her later when he realizes he’s wrong, Smita still thinks this whole plan is stupendously tone-deaf when it comes to what’s really inside Craig’s heart. We have heard her confess this to her sister, and her sister has been sympathetic.

Smita understands that there are bigger issues here, at least when it comes to the statement Harry and Craig are making. If you were to ask her under what possible circumstances would it be okay for Craig to kiss Harry again, she guesses this would be one of the few acceptable answers. She told them she thought it was crazy when they first told her about it (she thinks she was the first person they told, but really she was the second). And once they told her they were totally okay with it being crazy, what else could she say? She would always be on Craig’s side, no matter what, and if that meant helping them research and fill out paperwork and plan for this absurd feat of political statement and potential heart-endangerment, so be it. With the precision of the doctor she will no doubt one day become, she worked with them to plot out the best possible strategy for maximum endurance. This meant countless hours of watching YouTube videos of people kissing for very long periods of time. It was the strangest homework she’d ever done. But her regular homework was already completed; what else did she have to do?

Now here she is, and here they are, and now it’s closing in on the starting time. Once they start kissing, they will have to keep kissing for at least thirty-two hours, twelve minutes, and ten seconds. That is one second longer than the current world record for the longest-recorded kiss.

The reason they are all here is to break that record.

And the reason they want to break that record started with something that happened to Tariq.

We watch as he pulls into the parking lot. We watch as he sees them gathering—Harry and Craig, Mr. and Mrs. Ramirez. Smita, of course, and Rachel, who lives close enough to the school to walk. He sees them, but he doesn’t get out of his car, not yet. Because one of the trickier qualities of the mind is its ability to be in two places at once. So Tariq sits there and at the same time he heads back to the worst night of his life. Factually, three months ago. Emotionally, yesterday and today and three months ago and any period of time in between.

Blood in his mouth. It is like there is still blood in his mouth.

The guys were drunk, there were five of them, and while it wasn’t in this town, it was in a town close by. Tariq didn’t have his license yet, didn’t have a car. The movie was over, and he was waiting for his father to pick him up. His friends were heading out for pizza, but he had to get back. His father was running late, and the street became deserted once the end credits of the sidewalk conversations were over. There was someone in the movie theater booth, but that was it. Tariq couldn’t stand still, so he walked a little down the block, to look in store windows. When the other guys started shouting, he didn’t even know they were shouting at him. Ignoring them only made them pay more attention. By the time he understood what was happening, it was happening too fast.

He thought at first it was because he was black, but from all the variations of faggot they were throwing his way, he knew it wasn’t only that. And some of them were black, too. He tried to walk past them, head back to the movie theater or even to the pizza place where his friends were, but they didn’t like that. They boxed him in, and he felt the panic button being pressed. As they made fun of the color of his pants, as they taunted him some more, he tried to shove himself out. Threw his whole body into it, but there were too many of them, and they weren’t caught by surprise. They shoved him back in and he tried to shove out again, and this time one guy hit him, a blow right to the chest, and as Tariq bent over, more guys joined in. Because once one guy starts, it’s a game. Tariq fell to the ground, remembered someone telling him to curl up, to protect himself that way. They were laughing now, enjoying it, thrilled by it. He couldn’t even yell for help, because the only sounds he could make were ones he’d never heard before, a wailing, gutteral acknowledgment of the sudden, intense pain as they punched and they kicked, laughing their faggots at him as they broke his ribs.

Across the street, someone saw. The woman behind the counter of the Thai restaurant came running out, yelling and waving a broom. The guys laughed at this—laughed at her broom, at her broken English. But then two of the busboys came out behind her, and they heard her yelling police. Tariq didn’t see any of this, didn’t even hear it. He was trying to get his vision straight, trying to curl further into himself, trying to spit the blood out of his mouth. As far as he knew, they were there, and then, with one last kick, they were gone.

His father pulled up a minute later. Found him. Took him to the emergency room before the police arrived.

>

As he bled on the pavement, pebbles and gravel grinding into his wounds, we felt ourselves bleeding, too. As his ribs broke, we could feel our ribs breaking. And as the thoughts returned to his mind, the memories returned to ours. That dehumanizing loss of safety. It is something all of us feared and many of us knew firsthand. We are not unfamiliar with what happens next with Tariq—the long healing, the surprising concern from some (including his parents) and the unsurprising lack of concern from others (like some, but not all, of the police).

The assailants covered their tracks well, and were never caught. We know who they are, of course. Two of them are haunted by what they did. Three of them are not.

Tariq is haunted, too, although mostly he is defiant. “They beat the shit out of me,” he told people, soon after. “But you know what? I didn’t need that shit inside of me. I’m glad it’s gone.”

He will not let it stop him from going into the city, from dancing. But still, the fear remains. The bruises. And there in the back of his mind, residing just as they did in the back of our minds, are the most insidious questions of all:

How did they spot me? How did they know?

What did I do wrong?

People like to say being gay isn’t like skin color, isn’t anything physical. They tell us we always have the option of hiding.

But if that’s true, why do they always find us?

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

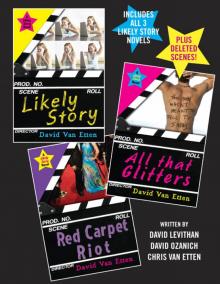

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!