- Home

- David Levithan

Someday Page 7

Someday Read online

Page 7

I tell myself to stop.

I don’t listen to myself.

Moses is on the shorter side and the slighter side—usually this is helpful when it comes time to be invisible. But for whatever reason, people keep seeing him and shoving him. It’s like a reverse game of pinball, where the pinball stays on a straight course and it’s the bumpers that move toward him.

It’s a little better out of the hallways. But not much. In math class, the guy behind me keeps poking my back with his pencil. The first time he does it, I startle—which he thinks is hysterical. It doesn’t take me long to find that the guy’s name is Carl and this is a regular occurrence. I don’t find any memory of Moses fighting back. So I just sit there and take it. I look around for some sympathetic looks, but no one seems to care. Moses is not the only one who’s used to it.

At the end of class, the teacher asks for homework to be passed up to the front of the room, and I can’t find Moses’s in his backpack. Meanwhile, Carl is shoving his paper in my face, telling me to pass it up. I want to rip it into shreds. I want to shower the shreds over his head. And at the same time, I want to know why I’m letting him get to me. It’s like my navigation through the day has been stripped of any possibility of autopilot. I need autopilot.

The bell rings and Carl takes a bottle of Gatorade out of his bag, opens the cap, and pours the contents into my backpack. I don’t even see it happening at first, I’m so mad at myself about the homework. Then I see him dropping the empty bottle into my bag, and I remember that Moses’s phone is in there. Even though I know I should not engage, I take the bottle out of my backpack and hold it by its neck and swing it at Carl’s laughing face. It’s a plastic bottle, and the damage I do is minimal, but his surprise is immense. Now people are paying attention, and are yelling that it’s a fight. But I don’t want to fight, I just want to save the phone, so I go for my backpack, which gives Carl the opening he needs to throw me to the ground. I can feel myself being lifted, just for a second, and then I’m falling and I’m hitting and he’s yelling that he’s going to hurt me. The teacher’s coming over now, and Carl is claiming self-defense. School security comes and is only slightly less belligerent than Carl. I am marched to the vice principal’s office, and the whole time I’m trying to dry off the phone—I’m actually asking if there’s any way to get a bag of rice from the cafeteria, because I’ve heard that rice can help, but the security guard is completely ignoring anything I say. I look behind me, assuming I’ll see Carl marched in the same formation. But apparently I’m the only one being corralled. It’s the time between class periods now, so the halls are full. People look confused to see me being pulled along by security. I can see a few asking their friends who I am.

The phone won’t turn on. My backpack is leaking a trail on the linoleum floor of the hallway. The security guard is yelling at me to put the phone away, asking me what the hell I’m doing, as if having a dead phone out is an admission of guilt in all things.

I am shown into the vice principal’s office. He’s on the phone, and when he hangs up, I realize the call was about me, because straight off he says, “So…you hit a fellow student with a bottle.”

“It was plastic,” I tell him.

This is the wrong thing to say.

“I don’t care if it was made of feathers,” the vice principal fumes. “This school has zero tolerance for violence. Zero.”

“Please,” I say. “Let me give you some context.”

I know there’s a twisted code of honor about never tattling on another student, never speaking up against someone who’s done you wrong. I know I will only make it worse by breaking this code. But the code of honor was written by bullies for the protection of bullies, and I don’t want to follow it.

I tell the vice principal what happened. I tell him about all the abuses Moses has put up with from Carl and his friends—every single one I can find in Moses’s memory, leading up to today. When I tell the vice principal how the bottle came to be in my hand, I see him look at my bag and the pool of Gatorade gathering underneath it.

“I apologize for snapping,” I tell him. “I know that was wrong. But I couldn’t take it anymore. I had to protect myself.”

“Carl Richards says he was protecting himself,” the vice principal points out.

“Yeah,” I say, gesturing to my body. “Because I’m so threatening.”

The vice principal snort-laughs at that, then collects himself, picks up his phone again, and says, “Please find out what classroom Carl Richards is in now and have him sent to see me in five minutes. Thank you.” When he hangs up, he looks at me for a hard few seconds before saying, “Alright. I want you to go see Ms. Tate in the guidance office. Tell her everything you told me, and anything else you might come to remember. Then wait there until the end of school. I’ll talk to Mr. Richards and hear his ‘context,’ and then Ms. Tate and I will discuss our next steps. This is a very serious matter, and I am taking it very seriously.”

“Thank you, sir.”

I pick up my dripping bag and start to head out.

“You also have permission to go to the men’s room to dry that off. The guidance suite has carpeting.”

“Understood, sir.”

I know I have to get out quick, because I don’t want to run into Carl again. Which is cowardly of me, because Moses will have to face him eventually—and since I’m the one who messed up, I should shoulder the initial, inevitable blowback. But I dodge, because I can.

The bathroom is empty. I use about forty paper towels to dry everything off. Some of the books have pages stained orange, and anything that was sitting at the bottom of the backpack—a small notebook, a pack of gum, another granola bar—is now the consistency of pulp.

I try turning on the phone again. Nothing.

I want to go to the library, to use the computer to check Facebook.

Then I remember, no—I have to get to the “guidance suite.”

The minute I walk into Ms. Tate’s office, she says, “Moses, this isn’t like you. This isn’t like you at all.” I am not surprised that she would say this, but I am surprised that she knows him enough to make the distinction. They’ve clearly talked before, but never about the real problems. Now I have to tell her what I’ve already told the vice principal—and as I do, she looks more and more concerned. I don’t have time to verify it, but I imagine that Moses has only gone to the guidance counselor before to talk about grades and colleges.

“I see, I see,” she says when I’m done. Then she closes her eyes for the slightest of moments, breathes in, and resumes. “Look. You are a smart boy, Moses. And you did a stupid thing. But part of being smart is doing stupid things and learning from them. We do have a zero-tolerance policy at this school about violence. And we also have a zero-tolerance policy about bullying. When those two policies collide—well, it calls for a little tolerance on our part. But whatever happens—and it’s truly out of my hands—you must never attack anyone else here ever again. Period. Is that clear?”

I nod.

“Good. Now give me your phone. I’m going to see if Mary in the cafeteria can spare some rice. I hear that’s the best shot you have. Sucks up the moisture. You’d have to ask Mr. Prue in chemistry for the specifics.”

She leaves, and I sit there alone for a few minutes. Her computer is on, and I wonder if there’s time to check Facebook and then erase the history. It feels like too much of a risk. A ridiculous risk. In fact, I can’t believe I’m thinking about myself at a time like this. Whatever the vice principal decides, I have made Moses’s life worse than it was before I came into it. If I’d been focusing on him and not on myself, I would have had the homework, and my backpack probably would have been zipped. I would have thought for a second about its placement and I would have been sure to keep it out of Carl’s reach.

Ms. Tate returns with a bag full of rice, and assures m

e that my phone is somewhere in the middle of it. She says to let it sit like that overnight. There’s only a half hour left in school now, and she tells me to read in the corner until the bell rings. I pull out one of my books, and she sees the wet warp and orange taint of the pages.

“Oh dear,” she says. “Can you still read it?”

“It’s mostly on the edges,” I tell her. The pages are hard to turn, and I’m not really registering any of the words, but I make sure to act like I’m reading so I don’t have to talk to her anymore. Eventually she seems to forget I’m there, even when she calls the vice principal to ask what’s to be done now. I don’t hear his answer.

I wonder if Moses’s parents will be called. From his memories, they seem like reasonable people. But this is not a reasonable thing their son has done, so there’s no precedent.

When the bell rings, Ms. Tate tells me, “Be here before homeroom tomorrow—let’s say seven-fifteen. We’ll discuss next steps then. I would advise you not to take the trouble you’re in lightly, and to think long and hard about what you’ve done. This is not to excuse Carl from anything that he did—but there have to be methods of dealing with him that do not involve fighting in school.”

I don’t challenge this point. But the question lingers, and I think both Ms. Tate and I feel it: What would those methods be? How do you stop someone like Carl, short of taking him down?

My guess is that the fight was not spectacular enough to merit school-wide gossip, because I make it to my locker unimpeded. I feel that if word had spread, Moses’s sister would have tried to get in touch with him. Although for all I know, she’s texted repeatedly.

It’s not that far of a walk home—fifteen minutes tops. I can’t map it or anything, so I rely on Moses’s memory. As people board buses and get rides, I try to make myself unremarkable. A lot of people are walking in the direction of Taco Bell and McDonald’s, so I veer down a side alley. I’m eager to get back to Moses’s computer, behind the closed door of Moses’s room. I am trying not to think about what it will be like for him when he wakes up tomorrow morning and realizes he has to get to school early to see Ms. Tate for the verdict on whether he’ll be suspended or expelled.

I hear a car coming and step to the side so it can pass. But instead of passing, it pulls up beside me. I turn and see someone who looks a lot like Carl—his brother?—in the driver’s seat, and then Carl in the passenger seat and some other guys in the back. The car turns into me, blocking my way, and stops. I turn around to run, but they’re already jumping out of the car.

I am so, so stupid.

“Hey, Cheng!” Carl’s brother calls out, slamming his door. “Think you’re tough, crying all over Petty’s office? Think it’s okay to attack someone in class, do you?”

He’s at least nine inches taller than me and might weigh twice as much. There’s no way this is fair.

“Fucking Cheng,” Carl snarls.

I don’t like the way they’re using my last name.

“Ready to fight now?” Carl’s brother taunts. “Gonna break out your karate moves?”

I want to leave my body, which isn’t even my body. I want to be able to leave while what’s about to happen is happening. Flight and fight aren’t really options. That leaves fright.

Protect your head.

I have no idea where I learned this. But when the first blow comes—Carl’s brother steps aside and makes Carl do it—I don’t try to strike back. I don’t open myself up by lashing out. No, I roll up and protect my head. I try to use the wall next to me to cover as much as possible. They start to kick me then, in the side. It hurts. A lot. But I am protecting my head. Moses’s head.

I hear shouting. The kicking stops. There’s more shouting. I can feel them moving away from me. Something soft comes and presses against me. The car doors open and slam. The engine starts. I open my eyes. It’s a dog—there’s a dog next to me. “Are you okay?” a woman is asking. She has her phone in her hand. I think it’s to call the police, but instead she says, “I got the whole thing. I got pictures of all those guys.” I’m trying to sit up, but it really hurts. I wipe my forehead and there’s blood.

“Okay, okay,” the woman says. “Don’t move. I’m calling an ambulance.”

I start crying. Because I’m hurting, yes. But also because I’ve done this to him. I’ve done this.

More people are gathering now, asking what happened. One of them says he’s a doctor and heard the shouting from his office. He checks me out and gets me to stand. We go to his office and he stops the bleeding, explaining that it’s just a cut, that I’m going to be okay. It looks worse than it is.

Then he checks my side and tells me I may have broken a few ribs. Tells me to lie down. Asks me for my parents’ number.

I try. But I don’t know it.

I explain about my phone, and I probably seem incoherent at first, answering What’s your parents’ phone number? with something about rice. But eventually the bag of rice is retrieved from my backpack. They take the phone out—too soon. It doesn’t work.

I tell them to call the school. To ask for Ms. Tate.

When they think I can’t hear, the doctor and his assistant say they can’t believe that kids today don’t know any phone numbers. I want to go to sleep. But I force myself to stay awake.

The ambulance arrives and I’m taken to the hospital for X-rays and for treatment. About ten minutes later, Ms. Tate comes in and says my parents are on their way. I look behind her and see my sister in the hall, crying. I wonder if she’s going to blame herself, for letting me walk home alone even though I told her it was going to be okay.

When my parents arrive, my sister stays in the hall. My mother is focused on how I’m feeling and what the doctors have said. My father is seething, and tells me that the boys who attacked me are being arrested as we speak. Apparently the video caught all their faces.

I should be comforted by this. But there is nothing that feels like comfort to be experienced. There’s only pain and guilt and sadness and monumental remorse.

I used to think I was good at this.

I am not good at this.

I am dangerous to anyone I’m in.

Moses’s mother studies his face. The next time the doctor comes in, she asks her if it’s okay for me to sleep.

“There’s no sign of a concussion,” the doctor says. “Let’s just finish here, then you can take him home and he can sleep.”

So at least I protected my head.

No, not my head.

Moses’s head.

* * *

—

They give me painkillers. I take them. As soon as I get into bed and my mother turns out the lights, I crash.

I wake up in fits and starts over the next few hours. Either my father or mother is watching over me. My sister has expressed sympathy but has kept her distance.

I don’t have the energy to say anything, or even the energy to figure out if there is anything I could possibly say. Sleep pulls me under soon enough.

This body is done with me for today.

A

Day 6089

It feels unfair to wake up the next morning as someone else.

Gwen has type 1 diabetes and an insulin pump, so I know I will have to be extra attentive—what’s second nature to her is not going to be second nature to me. I feel like I’m betraying Moses by not thinking about him, about what might be happening to him, but I know it’s more important to pay attention to Gwen and what she’s going to need for the day. Staying in bed and feeling awful is not an option. I will have to get out of bed, be social, monitor my blood sugar, and feel awful.

There’s a knock on the door.

“Are you up?” a voice—Gwen’s mother—asks. Then she adds, “We’re all waiting for you downstairs.”

She says it sweetly, so I know I’m not in tro

uble. I feel I should be in trouble.

But not Gwen, I remind myself. She didn’t do anything to Moses. You did.

I pull a robe over my pajamas and open the door. There are excited noises coming from downstairs. The kitchen, Gwen’s memory tells me.

I swing open the door and there’s a cheer of “Happy birthday!” Gwen’s parents are there, as well as four younger kids who don’t share any family resemblance in their features but deeply resemble a family in the way they exist with each other. There are cookies on the kitchen table that spell out H-A-P-P-Y B-I-R-T-H-D-A-Y.

“Cookies for breakfast!” one of the kids shouts out. Santiago, age seven. He’s only lived here three months, so this must be his first birthday celebration here. Cookies for breakfast is this family’s thing. “We made special ones for you!”

Santiago reaches for a cookie, but Alicia (age nine) stops him.

“Not yet,” she scolds. “We have to sing first.”

A spirited rendition of “Happy Birthday to You” follows.

Gwen (age seventeen) smiles. Because I make sure she smiles. Because I know she should smile.

But I feel more awful than ever. Why this, of all days? Why should I get to usurp a happy day, especially after I just caused an unhappy day for someone else? How is that fair?

And why am I expecting fairness?

Gwen’s family is so joyously excited for her. They love her so much. I try to allow that to take me in, to welcome me into my own expression of joy, because sometimes the only thing you have to pull you to a better place is the sheer force of invitation from the people who love you dearly. I know the fairest thing I can do for Gwen—other than leaving, which I can’t—is to try to give back to her family the affection that they are providing to her now, having no idea whatsoever that she’s not really here.

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

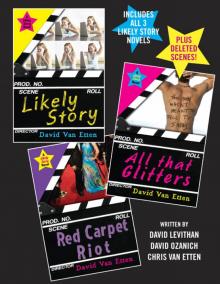

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!