- Home

- David Levithan

Someday Page 8

Someday Read online

Page 8

There’s no candle to blow out—I’m told there will be a big cake tonight. Now there are hugs and presents, until it’s time to go to school. Ozzie (age ten) wants me to wear an IT’S MY BIRTHDAY button on my shirt. Alicia tells him that buttons like that aren’t cool when you’re a teenager, which, she emphasizes, is something he should already know.

I almost put on the button to take Ozzie’s side. But I’m afraid of what the kids on the bus will say.

I head back upstairs to shower and change. In the shower, it all comes back to me—Moses in the hospital bed, the look of hate on Carl’s face.

It wasn’t your fault, I tell myself. It was Carl’s fault. And his brother’s. And all those guys.

I believe this. But I also believe that Moses would have been safe if he’d been navigating himself through the day.

After I’m dressed, I go online to make sure I know how Gwen’s insulin pump works. It’s the same kind I’ve had before, but I double-check. I also make sure to confirm the right levels from Gwen’s memory. At some point, I’m going to need to take a run, which is what Gwen does to make sure she gets the physical activity she needs. After school, usually.

I don’t go anywhere near Facebook. There’s no time. And I don’t deserve to see anything Rhiannon may have left me.

I figure I’ll have some time to think on the bus, but Gwen’s best friend, Connor, is saving her a seat. He throws little streamers in the air when she sits down, and the people in the seats around us wish Gwen a happy birthday. I realize I could have worn the button.

“I’m so excited for tonight!” Connor says. “It’s going to be such a great party! Your parents are the best.”

I don’t argue. Instead I think of Moses’s parents at his bedside. What they must be waking up to today. The conversations they must be having. His mother’s worry. His father’s anger.

We get to school and are soon joined by Candace and Lizette, Gwen’s other best friends. And Emily, Gwen’s other other best friend. Candace, Lizette, and Emily have decorated Gwen’s locker like it’s the biggest booth at a birthday convention—Gwen must love panda bears, because there are panda bears everywhere. And for presents, Candace, Lizette, Emily, and Connor have all gotten her picture books featuring pandas. (“Mine also features donuts,” Emily says as she hands hers over.)

Gwen says thank you. Gwen is blown away. Gwen tells her best friends how happy she is.

I am pretending. I am a fraud.

School is still school, and class is still class, but people are nicer when they have a chance to be nicer. Everyone seems to know it’s my birthday.

“Have you checked your Facebook yet?” Candace asks after Spanish class. “I left you the cutest panda pic.”

I take out my phone and check. There are so many birthday greetings. I could spend the whole day going into Gwen’s memory to figure out who all these people are.

“Isn’t that the cutest?” Candace asks.

I look at the photo—it’s a panda from the National Zoo cuddling a baby panda. They look like the happiest pandas I’ve ever seen.

“That’s adorable,” I say. Then Candace gives me a hug and heads to a classroom that isn’t mine. I have about a minute before I have to be in physics. I type Rhiannon’s name into the search field. But before I can click, Lizette is at my side, asking me if I saw the photo Candace left me, then asking me if we did the cookie thing this morning at home.

I use the minute I have to talk to her. Then I put away my phone.

Moses must still be in pain.

Moses must be wondering what happened.

Moses must be afraid to go back to school.

Everyone must be talking about what happened to Moses.

Maybe they’ve seen the video.

What will that do to him?

Emily blindfolds me on the way to lunch. She leads me, and I trust her. We don’t go to the cafeteria, but to a corner of the library. There, Emily leads my friends in what can only be called a choral birthday medley, with the Beatles’ “Birthday” song featured prominently. There’s an apple with a candle in it, surrounded by other apples. (“We know you’ll be getting enough cake later.”) My friends toast me with apples. Then we go to the cafeteria and get real lunch. They don’t let me pay for mine.

I want to get my phone. I want to go on Facebook and look for Moses Cheng. Even though I know he’s not going to post anything.

And Rhiannon. Even though I feel farther away from her than ever.

“Oh no,” Connor says. “She wouldn’t dare.”

I look up from our table and see a girl walking over. Before I can figure out who she is, she’s in front of me, holding out a blue box tied with a yellow ribbon.

“Here,” she says sweetly. “Happy birthday.”

Lizette puts out a hand to stop me from taking it.

“Uh-uh,” she says. “Dee, you are not invited to this party.”

“What?” Dee snaps back, all sweetness gone. “I’m not allowed to give her a present?”

Lizette stares her down. “The only present she ever wanted from you was some love and honesty. But you gave that present to Be-lin-da instead, and we do not allow regifting at this particular table.”

Dee pulls the box back. “Okay, fine.” Then she looks right at me. “You can’t say I never tried. This is me trying. And look at how well that goes.”

She heads off, and even before she’s out of earshot, Lizette, Emily, Candace, and Connor are all asking me if I’m okay, in a way that makes it clear that they are expecting Gwen to be a wreck.

“I’m fine,” I assure them. “I’m great.”

Which is true, because I still don’t know who Dee is.

Lizette high-fives me. “That’s my girl,” she says.

The mood turns even more celebratory, as if I’ve just vanquished a dragon.

They’ll all be so disappointed when it goes back to normal tomorrow.

Unless…

I get out of my seat.

“Where is she?” I ask, scanning the cafeteria.

Connor points to a corner. “There. Why?”

“I need to tell her myself. To never do that again.”

My friends look surprised, but they also look happy—and they aren’t stopping me.

I walk right over to Dee’s table. She’s already laughing with her friends, probably about me. When she finally sees me there, it’s her turn to look surprised. I notice the present is nowhere in sight.

“What?” she says. “You let them talk to me like that and then you come over here? What’s that about?”

“It’s about this,” I tell her. “It’s about me not needing them to tell you off. It’s about me telling you off firsthand, and telling you to never pull that shit again. I am done. Completely done. And I wanted you to hear it from me.”

I don’t give her time to respond. Partly because I’ve started shaking. Like my body is trying to tell me something.

As I’m walking back to my table, I can already see my friends cheering. They think I’ve done the right thing. I thought I was doing the right thing. But who was I doing it for? Gwen? Me? Moses? In the pit of my stomach, I’m wondering: What if she really loves Dee? But I don’t let myself check. What’s done can’t be undone.

“That was beautiful,” Lizette says as soon as I’m back in my seat.

“Best birthday resolution ever,” Emily chimes in.

“Best start of a birthday year ever,” Candace agrees.

And it’s Connor who asks it again: “Are you okay?”

I tell them again that I’m great.

But this time it feels more hollow than before. And I’m not even sure why.

* * *

—

Gwen has a lot of friends. They are there in the halls and in her classes. They are there on her Facebook

page. And they are all there at her house for the party that night.

Everyone in the family and many of my friends have chipped in with decorations, so it’s like every age I’ve already been is represented—construction paper cutouts and crayon drawings alongside a supercut of the past year playing in a loop on the TV screen. Friends laughing. Friends in costumes. Friends singing. Gwen at the center of it all.

I work hard to keep track of who’s who, but I can barely keep up. April (age four) hangs by my side and provides a good diversion, especially because a lot of my friends have to introduce themselves to her and explain who they are.

Then the moment comes when the lights are turned off and a cake is carried in, its eighteen candles (“One for good luck!”) flickering to show me all the friendly faces who’ve gathered to celebrate with me. “Make a wish!” Gwen’s mother calls out, and I want to wish for word from Rhiannon and I know I should wish for Moses’s speedy recovery, and I get tangled between the two and debate in my head for too long, to the point where they can all see me deliberating and they find it funny. I wish for Moses’s speedy recovery, and then the minute the candles are blown out, my belief in wishes is also extinguished, and I feel ridiculous for being so anguished and feel disgusting for taking Gwen’s wish and using it for myself.

As the cake is cut, I go to the bathroom, ostensibly to check my insulin (which is fine, even though I didn’t get a chance to run with everything going on, so I’m a little bit off). Really, I’m doing it to take myself out of this scene for a moment. Because it’s not my scene. When I was a kid, I could trick myself into thinking that the birthdays were really my own birthdays, that there was a direct, to-the-day correspondence between the age I was and the ages of the bodies I was in. Then, when I was twelve, it happened: two birthdays in the same week. And suddenly I realized that what was happening to me was neither precise nor predictable. The birthdays had never been mine.

A birthday—a real birthday—is yet another thing I will never have.

I tried to pick a day for myself. August 5th. That lasted for a couple of years. But ultimately it felt arbitrary, a lie I was telling myself to feel better. And the moment I saw the lie for what it was, it was hard to believe it.

So I taught myself not to miss it. To know I was different, and to accept that.

That worked better. But it’s not working anymore.

The sounds of a birthday party through a closed door are unmistakable: the colorful bubbles of conversation, the heartfelt laughter, the feet of small children running around the people acting like larger, older children. I recognize these sounds and know their chaotic delight, but only through a door.

I know Gwen has to return to the party. I know she’ll be missed if she’s gone for too long. Once upon a time, I didn’t know what that was like, to be missed. Now I do, and I understand why I can’t avoid the love being sent Gwen’s way.

I must dive back into the festivities. I must swim within the conversations, swim from gift to gift, wish to wish. Some people swim to get somewhere. Others swim to stay in shape, or to get faster. Right now, I’m going to swim so I won’t drown.

Comment from M:

This is pointless.

Comment from Someone:

I understand.

Comment from M:

Not possible.

Comment from Someone:

Listen to me first. I have depersonalization/derealization disorder. You might not even know what that is. I didn’t, until I found out I had it.

Like you, I have periods when I feel completely separate from my body and from the world around me. It’s a hard thing to put into words. The best I’ve been able to come up with is that it’s like everything you see is part of this video game. Only with a video game, you know you’re holding the control. But my DPD/DRD is like I’m watching the video game but I don’t have the controller. I am convinced that I’m an avatar, not a person. I am convinced that the divide between the massive number of thoughts in my head and the actions around me is too wide to be crossed. I’m not just isolated from the world; I’m isolated WITHIN MYSELF. My thoughts are the only active things that I can believe. And that can be very frustrating and very confusing and very painful.

For a while, I thought I was going crazy. It was only when I found out that what I was experiencing had a name and that I wasn’t the only one who had it (2% of the population has DPD in some form) that I could start to actually take action against it. It’s not possible to make it go away, but knowing what it is and how it works means I can contain it a little more—contain it by naming it, both to myself and to other people.

I am not saying you have DPD and/or DRD. But I am saying that whatever it is you’re facing, the odds are nearly 100% that there’s someone else who is also facing it. Acknowledging it and naming it and understanding it as much as it can be understood are the most important things you can do. You say you want to die. I felt that way, too. But you also don’t want to kill the body you’re in. That means you want to live. The fact that you’re talking about it—even with strangers—is a good step. You are on your way to acknowledgment.

Comment from PurpleCrayon12:

Thank you for sharing that, Someone.

Comment from M:

I appreciate what you’re saying. I do. But with me, it’s different.

Comment from Someone:

How?

Comment from M:

You experience separation from your own body. I am in a different body every day.

NATHAN

It’s not that I’m completely antisocial—I just don’t go out of my way to talk to people. At school, sure. I talk to friends. I talk to teachers when I have to. I talk to the guidance counselor when she “checks in” on me, even though what I really want to tell her is that in a high school where kids are dealing drugs and getting pregnant and beating the crap out of each other in the hallways, her attention would probably be better spent on other kids, not me.

Once school is done, I’ve usually run out of social energy. If my mother has asked me to go on some errands, I’ll do them. But otherwise, it’s straight home.

I’m walking home on Wednesday when a car pulls up beside me and a woman rolls down the passenger window.

“Excuse me!” she calls out. And honestly, my first reaction is to wish she’d try someone else. But there isn’t anyone else around, so I stop. I don’t say hello or anything, but she smiles and acts like I have.

“I’m a little lost,” she says. “I was hoping you could help?”

“Sure,” I tell her. Though now I’m thinking, Can’t you just use your phone?

Before I can ask where she needs to go, she gawps at me and says, “Hey, aren’t you that kid who was possessed by the devil?”

Now I totally regret stopping, because this woman has to be in her fifties or sixties, and she must have better things to remember than a news story from three months ago.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I tell her.

“Of course you do! You were picked up at the side of the road. Said the devil got you drunk or something like that. It was hysterical!”

“I’m gonna go,” I mumble. Because something always stops me from being fully rude, I end up in this awkward state of halfway rude.

“Oh, don’t worry about it!” the woman calls out. “Vigilabo ego sum vobis!”

“Excuse me?”

“I’m sorry. I won’t bother you too much longer. Can you just give me directions?”

I want to get the hell out of there, but still: only halfway rude. So I say, “Sure. Where are you going?”

“Twenty Maple Lane,” she says, a glint in her eye.

That’s my address.

“What?” I say.

“As I told you, vigilabo ego sum vobis.”

What the hell? “I don’t know wh

at that means!” I tell her.

“You will!” she chirps out. Then she guns the motor and drives away.

At the end of the road, she turns in the direction away from my house. But I’m still nervous as I keep going. I almost call my mother, but I can imagine what her reaction would be if I told her she needed to come pick me up because some old woman gave me a taste of stranger danger. My credibility has already been shot. Even if I cry puppy, they act like I’m crying wolf.

So I walk home with my phone camera looking behind me so I can see if the car returns. When I get home, I’m there alone, so I lock all the doors.

Nothing happens.

I start to wonder if I misheard her. Maybe it was Maple Drive and not Maple Lane—our town has both, even though I don’t think either has a single maple tree.

I try to forget it.

* * *

—

Three days later, my mother takes me shopping for new pants.

I tell her I don’t need new pants. She points to the frayed bottoms of the khakis I’m wearing and tells me they are—her exact word—unacceptable. The way she says it, you’d think it’s a miracle that people don’t throw stones at me as I walk down the street. Underneath the tirade, I can hear the true sentiment: You’ve embarrassed us enough this year, haven’t you? Must you keep doing it? Of course, there’s no way she can erase what happened when A took over my life. But she can buy me new pants.

We go to the Gap. I find the same exact pants I’m wearing, in the same exact size. I imagine we’re done—but no. She says I have to try them on.

So there I am, peeling off my khakis so I can put on their better-loved twin. A pair of ankles and shoes appears below the changing room door—I figure it’s the salesperson asking me if everything’s fitting, even though I haven’t had enough time to put anything on. But instead, a young voice says, “Hey, Nathan…vigilabo ego sum vobis.”

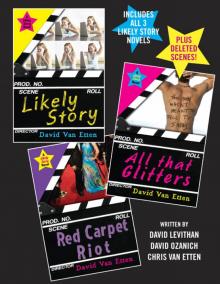

The Lover's Dictionary

The Lover's Dictionary Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story

Hold Me Closer: The Tiny Cooper Story The Full Spectrum

The Full Spectrum Two Boys Kissing

Two Boys Kissing Are We There Yet?

Are We There Yet? How They Met and Other Stories

How They Met and Other Stories The Realm of Possibility

The Realm of Possibility Love Is the Higher Law

Love Is the Higher Law 19 Love Songs

19 Love Songs Another Day

Another Day Every You, Every Me

Every You, Every Me Boy Meets Boy

Boy Meets Boy The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother)

The Mysterious Disappearance of Aidan S. (as told to his brother) 21 Proms

21 Proms Six Earlier Days

Six Earlier Days Wide Awake

Wide Awake Take Me With You When You Go

Take Me With You When You Go Someday

Someday You Know Me Well

You Know Me Well Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah

Sam and Ilsa's Last Hurrah Hold Me Closer

Hold Me Closer Likely Story!

Likely Story!